Detroit Before Edward Stiling – Part I

By Jeff Blakley

In the published accounts of the history of Detroit (now known as Florida City), Edward Stiling is portrayed as the founder of the town. The true story, as is always the case in history, is quite a bit more complicated. Stiling has achieved prominence in the historical record because he came to Florida City in 1910 and stayed there for the rest of his life. He, with four others from Detroit, Michigan, started a tomato canning plant in 1913; served as mayor from late 1916 to 1920, was active in agricultural and civic affairs in the area, was a well-known real estate agent and his daughter, Octavia, married Lee H. Lehman, who was a prominent businessman in Homestead. While he played an important role in the founding of Detroit, other men from Lawton, Oklahoma; Topeka, Kansas; Henry, Illinois and Knoxville, Tennessee also contributed greatly to the establishment of the town. James M. Powers and his sons worked for the Miami Land & Development Co., Charles S. Hough, from Lawton, Oklahoma, was the first marshal and helped establish the first church in Florida City, Dr. Benjamin F. Forrest, of Henry, Illinois was the first mayor and Andrew H. Love, from Tennessee, owned a real estate company, the Biscayne Bay Land Co., which promoted Detroit real estate in Knoxville. Then, there were all of the homesteaders who were busily selling off their claims for a tidy profit shortly after they proved them up. While Stiling did bring the first group of people to Detroit in October of 1910, there were plenty of other people whose presence contributed to the establishment of the town.

An article published in the Homestead Enterprise on March 30, 1923 gave a very brief history of Florida City up to that time. The anonymous author wrote that before the group of people from Detroit, Michigan arrived, “[t]here had been homesteaders there before them, J. S. Caves, the Hunters and one or two others, but there had been no organized development.”1 This statement is debatable, because Jesse S. Caves’ property was just outside of the future boundary of Florida City (as was Henry Brooker’s, who was not mentioned in the article and who filed his claim 2 years before Caves did) and William H. Hunter owned 10 acres of land within the future town but did not live there. There was a resident who did settle in what became Detroit in August of 1910, before the arrival of the group from Michigan. He was one of the “one or two others” noted in the article but he has never been mentioned in any of the histories published so far. His name will be revealed in part II of this article.

The F.E.C. Railway reached Homestead on August 30, 1904 and there was a brief halt to construction activity until April of 1905, when work began on the Key West Extension.

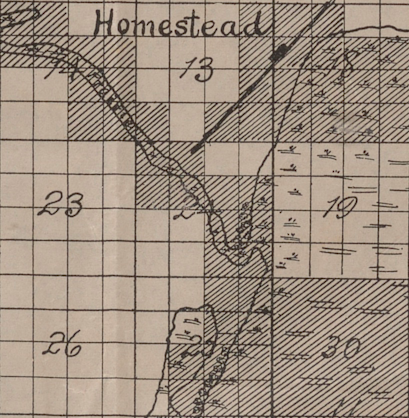

This map, drawn in December of 1903, shows the route of Flagler’s railroad extending southwest, past Homestead. When William J. Krome completed his exploration of the Cape Sable country in June of that year, his proposed route was not included on this map. Instead of going to Cape Sable, E. Ben Carter, the civil engineer in the Jacksonville headquarters of the F.E.C., in consultation with others, made a decision to stop at Homestead and explore other options. The route finally decided on was to go to Key Largo, passing through the small settlement of Jewfish, on the mainland just north of Key Largo. The railroad route turned south just past Homestead and proceeded south-southeasterly through the east half of the southeast quarter of section 13, crossed the land in the north half of the northeast quarter of section 24 (the two squares that are not marked with diagonal lines) claimed by Horace K. Roberts on September 6, 19042 and continued to a point a half-mile south of present-day East Palm Drive on the eastern boundary of section 25 and then took a more southeasterly turn down to Jewfish Creek.

The work of building the roadbed for the track-laying machine below Homestead was largely completed by African-Americans, but documentation of their contributions is not easy to find in the newspaper accounts of that time. An article that appeared in May, 1905 in The Daily Miami Metropolis stated that “[t]he operations now being pursued on the mainland south of Cutler, or Homestead, the present terminus of the road and consists of grading, fully one hundred or more negroes being engaged in the work. The better part of these negroes were secured in Jacksonville and came down a few days ago in a special car, which was switched from the main line to the extension and taken to Cutler without a change. The others were secured here and it is said that the company will continue until at least one thousand hands will be engaged in this great undertaking.”3 On July 25, fifty more negroes from Jacksonville arrived in Miami and were “taken to Homestead to work on the extension of the road from there to the coast4 and on October 10, “another large bunch of negro workmen for the Key West extension operations came in from the north.” They were “hastily transferred” from the train to the steamer Biscayne and “they were off to the wilds of the lower coast.”5

Three years of planning by John S. Fredericks, William J. Krome, Berte Parlin, William P. Dusenbury and many other civil engineers whose names are likely lost to history laid the foundation for the work that started then. The enormous project of building the Key West Extension started on Key Largo and Long Key and proceeded in both directions. Work on what is today known as the Eighteen Mile Stretch started from what would become Detroit in mid-September of 1905.

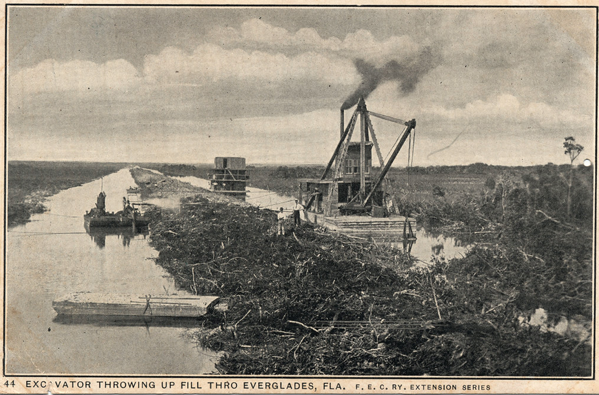

“The two dredges being built by the F.E.C. Railway at Homestead are now nearing completion and as soon as they shall have been done, they will be set to work cutting themselves out of a canal through the land eighteen miles or more in distance to Jewfish Creek, where they will emerge into the open waters of the coast. This canal will be mostly through prairie and low land and will follow the route of the railroad from Homestead to the coast, the soil removed being thrown up to form the bed of the road. The crafts will be launched into miniature pools, or lakes, already dug for them and from which they will begin their trip through the land to navigable waters.”6 These dredges had no name – they were simply designated as “Dredge No. 1” and “Dredge No. 3.” After completing their work, they were towed down to Long Key, where they were put to work building the viaduct there.7 There were two additional dredges, the Mikado and the John Babcock, that worked their way north from Key Largo. The dredges completed their work in early July of 1906 and the rails reached Jewfish Creek on December 1.8

With the completion of the tracks to Jewfish, engine No. 11 was dedicated to bring supplies from the Miami Terminal Docks in January of 1907 and the bridge across Jewfish Creek was placed in service on February 5, 1907. This was an important achievement, because supplies were now routed directly to Jewfish Creek, shortening the route to the Keys by 50 miles.9

The country south of Homestead was now easily accessible. All of the land eligible for homesteading within one mile of the Homestead F.E.C. depot had been claimed by the end of 1906 so this area became the new center of homesteading claims. A rough trail was cut through the virgin Dade County pine forest following the section line that became Palm Avenue towards the Everglades and numerous homestead claims were filed, starting in 1910, west of what was to become the town of Detroit.

Very little documentary evidence of the earliest arrivals in the Detroit area has survived. It is likely that much of the hard labor of cutting down trees to create rough roads in the area and clearing land for crops was done by African-Americans. The 1910 census of Homestead, which is one of the few sources of information for this period of time, must be used with great caution because enumerators were not able to accurately count people in such a newly-settled and rural area. For Homestead, 18.8% of those enumerated were African-American. That compares with 23.6% in Princeton, 12.5% in Redland and 25.2% in Silver Palm. Silver Palm in 1910 probably included Goulds, which became a separate enumeration district in 1920. The boundaries of the enumeration districts are not known, but the higher percentage of African-Americans in Princeton and Silver Palm likely reflects the existence of the Drake Lumber Co. in Princeton and the fact that Goulds10 11 was intensely farmed using African-American labor. In 1920, comparable percentages were 28.6% for Florida City, 26.7% for Homestead, 23.9% for Princeton, 51.1% for Goulds, 11.7% for Redland and 10% for Silver Palm. Nationally in 1910, the percentage of African-Americans stood at 10.7%.12 There were African-Americans who lived in what is now Florida City before 1910 but there is no documentary evidence of it. There is only scant evidence of White settlers in that area before 1910. Those few White settlers will be the subject of the second part of this two-part series.

______________________________________________________________________

- Homestead Enterprise, March 30, 1923, Section 3, p. 2. This edition was a celebration of ten years of history, in three sections.

- Excel spreadsheet of homestead claims

- The Daily Miami Metropolis, May 12, 1905, p. 1

- The Daily Miami Metropolis, July 25, 1905, p. 4

- The Miami Metropolis, October 10, 1905, p. 4

- Miami Metropolis, September 8, 1905, p. 5

- Miami Metropolis, February 26, 1907, p. 1

- Florida’s Great Ocean Railway, by Dan Gallagher, Pineapple Press, Sarasota, Florida, 2003, pp. 66-68

- Florida’s Great Ocean Railway, by Dan Gallagher, Pineapple Press, Sarasota, Florida, 2003, pp. 68-69

- Early Agriculture in Goulds

- The Story of Baile’s Road

- Wikipedia

Great article Jeff. Looking forward to Part II.

Thank you for the research! Great article.

What’s happened in the last one hundred years is spectacular and would be even more so if Henry Flagler’s train route was still operating. Thanks Jeff, for your historical research.

Thanks, Jeff for another great article in an attempt to flesh out South Dade history and include all segments of the population.

Remarkable detail. Thank you for another fine work of our history and I am very much looking forward to Part II.

Question: Dusenbury Creek in Key Largo is quite similar in name to: William P. Dusenberry referenced in Part I. Could there be an orthographic incongruity in the historical record somewhere?

Thank you for catching my spelling error! Dusenbury Creek on Key Largo is named for William P. Dusenbury, a close friend of William J. Krome.

Thank you for the clarification that our beloved Dusenbury Creek here in Key Largo was actually named after William P.

I will share this with my Coast Guard community family & friends!

If you click on the Berte Parlin link in the article, you will learn that William P. Dusenbury survived the sinking of Quarterboat #5 at Long Key after it was swept out to sea by the hurricane of October, 1906.

Enjoyed another great article with A+ research.

Excellent job, as always, Jeff. Looking forward to spending more time with this site.

Great article Jeff, loved reading about the history of Homestead. Too bad I didn’t pay a little more attention to it growing up. Can’t wait for part II.

Great job!

I downloaded the spreadsheet you made of early land claims in the area and I was fascinated at the names that I recognized. Never knew the people who I grew up with were descendants from the early settlers. The next time I see them I will ask about family.

What I found intriguing, after I had compiled the information, was the number of women who had filed homestead claims.

My memories go back to the mid 1950’s…It is hard for me to believe just how much of the area was developed in the 50 years before me. I suppose back then 50 years seemed like a lifetime. It helps me understand the development of the area since 1950…Just as people who lived in the area in 1900 would not recognize it in 1950, I cannot recognize parts of the town today….I wonder what the area will look like in the future 50 years or so…