John Ulric Free – Part II

by Jeff Blakley

In Part I, I provided some genealogical information about J. U. Free and his family. In this part, I will delve into Free’s business ventures.

John Ulric Free’s father died when he was just three years old. After her husband’s death, his mother, Emma Adeline, the daughter of a well-to-do farmer in Meriwether County, married Charles J. Burton, a member of another prosperous family in Meriwether County. Charles’ grandfather, Isaiah (1796-1877), owned real estate worth $10,000 in 1850 in Warnerville, not far south of Senoia.1 Charles’ father, James N. (1835-1922), was a bookkeeper in Atlanta in 1900.2

John U. Free, Jr. joined the U. S. Army in 1898 at the age of 17 and gained experience as a pharmacist while serving in the Spanish-American War in Cuba. His step-father, Charles J., was enumerated in Atlanta in 1910, where his occupation was given as a “meat dealer.”3 Free grew up in a mercantile family and took that experience with him. After he was discharged from the Army, he returned to Georgia, where he married Lulu Belle Carmichael in 1904 and began his business career in a drug store in Kestler (now Damascus), Georgia.

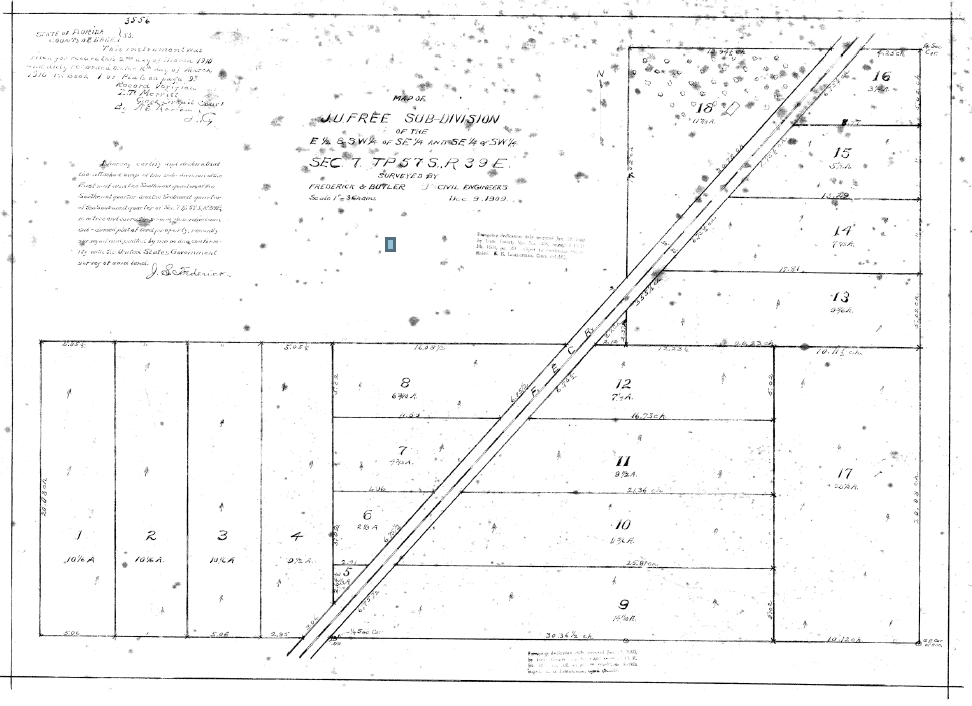

After spending a short time as a clerk in the drug store and then, as the owner of a grocery store in St. George, Free, like thousands of others, saw opportunity in being part of the building of Henry Flagler’s Key West Extension of the Florida East Coast Railway. He hired on and claimed his homestead, as related in part I of this article. Like hundreds of other homesteaders all over Florida, Free was also a real estate speculator and a developer. In November of 1909, before Free had obtained the patent on his property, he had his homestead surveyed by Frederick & Butler4 and divided into 18 parcels.

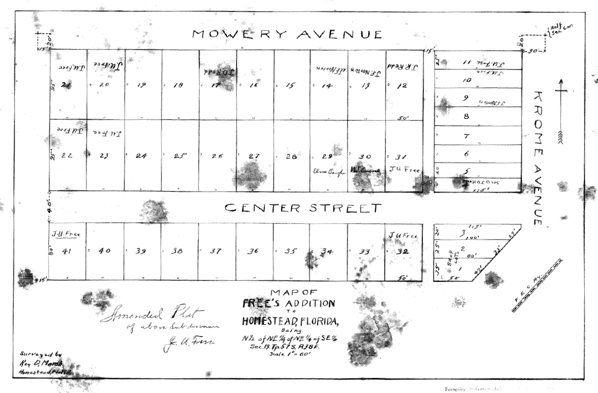

The first building that J. U. Free built in what would become the Town of Homestead, a grocery store, was located on Railroad Avenue on lot 5 of block 3. As more people flooded into the area, Free purchased the five acres at the southwest corner of Mowry and Krome for $420 from Ulysses A. Knight and platted it as J. U. Free’s Addition to Homestead in 1911.5 Knight was a real estate speculator who had purchased the land from the Model Land Company.

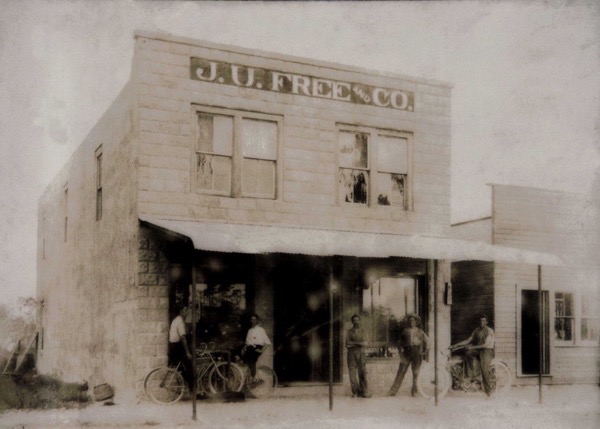

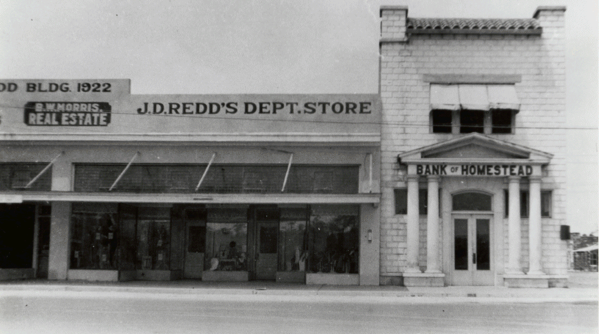

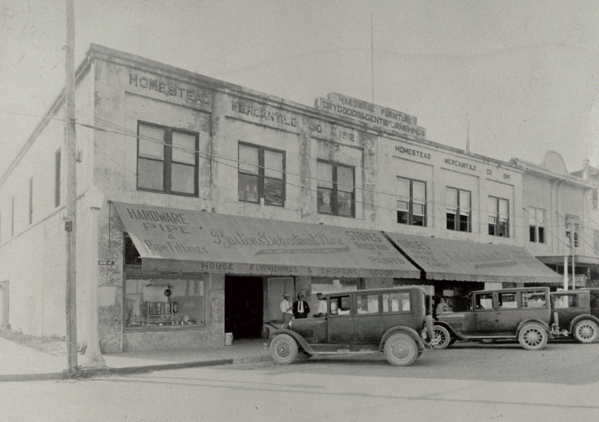

Free then erected this building, the first concrete building in Homestead, in late May of 1911.7 Initially, his new two-story building was the location of J. U. Free & Co. but he sold the store to C. J. Denham & Co. in early 1913. Denham, in turn, sold it to William B. “Bunny” Caves and Henry Pridgen a few months later and then Caves sold his interest to J. D. Redd so that by September of 1913, the building became the location of Redd & Pridgen, dealers in men’s furnishings.8 In October of 1914, Henry Pridgen sold his interest in the store to J. D. Redd.9

This store is where the Dade County Telephone Company was located, on the second floor.[ibid.] Free was one of the directors of the company, established on May 22, 1911.10

Upon completing this building, Free sold his grocery store on Railroad Avenue to Walter J. Tweedell.

By 1922, Redd had purchased the adjoining wooden building, torn it down, and built his department store.

The lot that the Bank of Homestead was built on was donated by J. U. Free.11

The Bank of Homestead building, along with all the other buildings on the block, was demolished by the City of Homestead in 2017 to build Homestead Station.

In May of 1912,12 Free sold lots 11, 12 and 17 of his homestead, a total of 37 1/2 acres, to Stephen M. Alsobrook of Dania for $1,000. Considering that Free had paid .87 per acre for his homestead less than 5 years before, he did very well indeed, selling the three lots to Alsobrook for $37 per acre. Alsobrook then sold the property to E. M. Martin, who also acquired lots 9 and 10 of Free’s homestead and platted it in 1913 as the Woodlawn Addition to Homestead. Also in 1913, Free platted lots 1-4 of his homestead as J. U. Free’s 2nd Addition to Homestead.

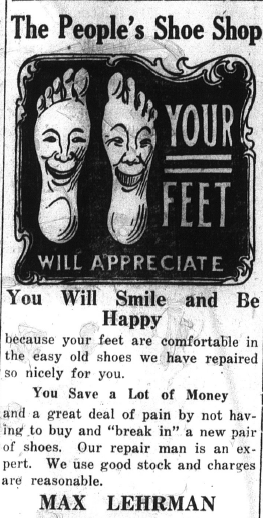

In the fall of 1912, J. D. Redd built a store on his lot south of the Free store for Max Lehrman, a Jewish merchant from Key West,14 who opened the People’s Shoe Shop.

Lehrman was one of the charter members of the Homestead Chamber of Commerce when it was organized in July of 1915,16 but left Homestead for Fort Lauderdale four months later, in November. There, in partnership with J. U. Free, he established the Free & Lehrman Department Store. In July of 1916, Free, his wife and their three children spent the night with Lehrman in Fort Lauderdale and then continued on with a combined vacation and business trip, traveling to the “the north and west” in his car. He met Lehrman in Baltimore in mid-August and went with him to New York City, where they purchased the “fall stock for both their stores here and at Homestead.”17

Active in the Methodist Church, Free was largely responsible for the erection of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, which was located on the southwest corner of N.W. 1st Avenue and 2nd St. He put his employees to work building the church, which held its first services on June 27, 1913.18 In November, he attended the quarterly conference of the Methodist Church in Fulford.19

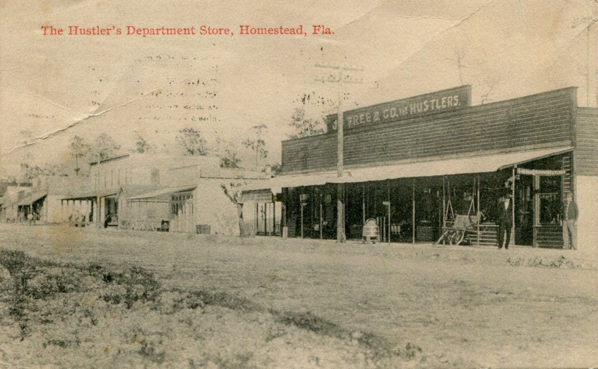

Ever the hustler and very successful in selling goods to the increasing number of people in Homestead, he sold his building on S. Krome Avenue in September of 1914 to B. E. Willis of Ft. Lauderdale and added a 20′ x 75′ addition to his already large department store on Railroad Avenue, south of the Evans Hotel.20

The sign on the front of the store reads J. U. Free & Co. The Hustlers. The two-story building with the porch, near the left side of the photograph, is the Hotel Evans, now the Hotel Redland.

By early 1914, Free’s business empire had grown so large that he needed help. He asked his half-brother, Joseph L. Burton, to come down and be the manager of his store. By summer, Burton was in town and was put in charge of the grand opening of the new store on August 1, 1914.21

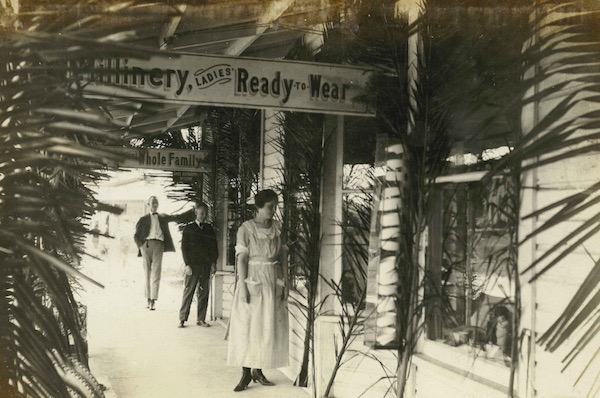

This photograph is of the original wooden building, taken in 1921, and shows J. U. Free’s Arcade, composed of a number of small businesses.

In December of 1914, Free relinquished his seat on the Town Council and ran for Mayor but lost to Frank Bartmes in the election held in early January of 1915.22

By July of 1915, Free was doing so well in business that he left for a three-month trip across the United States, leaving his family in Homestead. He traveled by train and boat and visited Mexico, Alaska and Canada before returning to Homestead in September of that year. The trip cost him about $500, which is about $13,100 in 2020 dollars.23 While he was gone, Burton was managing the store and adding businesses to the building. P. Weinburg, who owned the Diamond Palace in Key West, opened a shop, which was managed by I. Meltzer.24

In January of 1916, an anonymous writer, perhaps displaying a bit of jealousy, noted that “J. U. Free has a new Ford. Having enough money to buy a car after putting up the cash for fertilizer for 20 acres planted in tomatoes would indicate that he is living somewhere near Easy street …”25

In addition to his store, Free was also selling real estate and building houses for sale and for rent. In late 1916, he placed a quarter-page advertisement in the Homestead Enterprise with listings for 21 properties26 with this statement at the bottom:

“Who is J. U. Free? He is not a real estate dealer but actual owner of the above property. The fellow who has built more houses in Homestead than any other five men, and who has sold part of them for less money on first cost than anyone else in town. I have over a hundred lots and will sell any of them cheap to parties who will put up actual improvements. Don’t by any means buy unless you look me up. Where can you find me? Hard to tell as I am a busy man, but ask Joe Burton. He can tell you where to find me. It’s money in your pocket to hunt me up.”

Owning a store, selling real estate and being involved in the local political scene wasn’t enough for Free, though. In 1919, the Homestead Growers’ Exchange, a cooperative agricultural marketing business, was organized and Free was elected as the chairman of the Board of Directors.27 He had cropped since he had arrived in Homestead but by 1920, he owned 250 acres in Highland, which was where the Mexican-American housing complex is located southwest of Florida City, just west of the prison. A “good-sized packing house with accommodations for 23 packers … built of lumber cut on the grounds…” was built to handle the crops raised in the surrounding area.28 Free also had a commissary where his employees could purchase “necessary provisions” and a “good boarding house for white help at not over $8.00 per week”29 on the property. During the 1920-1921 farming season, Free leased 40 acres of his property to six Hindus, who “were real workers,” harvesting 400 crates per acre, “all through hard work.”30

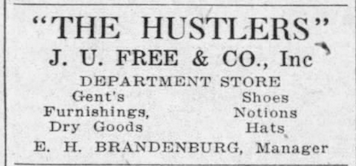

In 1921, Joe Burton and J. U. Free dissolved their partnership and Burton moved into the north half of the ground floor of the new Horne Building on Krome Avenue, where he opened Burton’s Department Store.31 Early in 1922, Free reorganized his company and capitalized it at $30,000.32 He invited Emory H. Brandenburg, Sr., who came down from Griffing, Georgia, to be the manager of his business.33 In 1923, Emory married Nina Scott, the daughter of Free’s wife’s sister, Jipsie Mae Carmichael.

A new concrete building was erected on the north side of the wooden building, adjacent to the new Homestead Bakery building,34 which was erected before 1921 by J. E. McDonald, another developer in early Homestead.35 In the photograph below, taken in 1921, the building at the left side of the photograph is the hotel. Free erected his new building where the Meat Market, which was owned by Arlie and John Tucker, of Adel, Georgia, is shown.

In later years, the former Free Building was the home of Churchman’s Furniture. The building, built of poured concrete on the first floor and tile block construction on the second,36 was demolished in 1993 in the demolition derby after Hurricane Andrew.

As early as 1914, Free had incorporated the phrase “The Hustlers” into his store name and that is how he continued to advertise his business in his new building.

The grand opening of the new store took place on July 20, 1923 with a supper and dance.37

Free had sold real estate since shortly after he arrived in 1907. Real estate sales had been growing steadily since at least as early as 1912, when the Bank of Homestead was established to provide capital for real estate speculators. By 1925, sales had accelerated to the point where Free sold over $50,000 ($744,000 in 2020) worth of real estate in just 10 days in early March.38 By the summer of that year, Free had sold his house on the Dixie Highway to a syndicate who put it on the market as Desoto Heights,39 got on board with a proposal to create Redland County out of the southern portion of Dade County40 and was elected president of the Homestead Bond & Mortgage Co., organized on April 3, 1925 and capitalized at $250,000.41 Edward Stiling and W. D. Horne were added as directors a week later.42 In mid-April, with the real estate market booming, the Homestead Realty Board was organized. Free was a director and one of 31 members.43

In February of 1925, Free purchased the hardware department of the Homestead Mercantile Co.44 and then sold it in late 1926 to his half-brother, Joe Burton. Burton had previously gained control of the rest of the company and changed its name to Burton’s Department Store.

Courtesy of the Florida Pioneer Museum

The 1926 hurricane, which made landfall at Cutler, due east of Perrine on September 18, is remembered in history books as the hurricane that destroyed Miami. It is not well-known that the center of the hurricane passed over Perrine and thus severely damaged the southern portion of Dade County as well. Free, along with many other businessmen and farmers, suffered large losses from which many did not recover. Free was one of them: he filed for voluntary bankruptcy on October 12, 192745 and the assets of his business were liquidated by March of 1928.46 Free still had considerable assets, though, enabling his wife and children to take a two-month motor trip to the northern states in the late spring of 192847 and Free to take a separate vacation later that summer to New England, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.48

A few months after he returned, Free underwent a “serious operation” at the Post Graduate Hospital.49 The operation, which was performed to discover the cause of the severe pain which he had been experiencing, revealed an advanced stage of liver cancer, which resulted in his death on November 11. His funeral, at the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, was attended by hundreds of mourners and he was buried at the Palms Cemetery with full military honors.50 Unlike other prominent men who died in the Homestead area in the 1920s, Free’s funeral was not attended by the Ku Klux Klan.

The KKK was very active in the Homestead area in the 1920s. 200 members attended the funeral of Charles D. Bryant, the Homestead Town Marshal murdered by William “Grey Eye” Simmons on June 15, 1923.51 Scores of Klan members attended the funeral of Thomas A. Collins, a businessman in Modello, who was killed in an auto/train collision on November 20, 1923.52 and dozens lined the path to the grave of Lindley Hoffman Livingston, who died on May 4, 1924. Lindley was the brother of Anthony R. Livingston, a prominent civil engineer in Homestead. Members from all over Dade County also attended the funeral of George W. Moody when he died on December 23, 1927. Even though Free worked in close association with Lawrence W. Taylor, the secretary of the Homestead chapter of the Ku Klux Klan,53 no documentary evidence has been discovered that stated or hinted at Free’s membership in the Klan.

The story of John U. Free, who came here in 1907 and died in 1928, is all too common in the history of this area. A prominent businessman in life, he was largely forgotten within 10 years of his death. The census of 1930 showed 2,905 people living in the Homestead precinct. By 1935, that number had increased to 3,901 and in 1940, to 4,063. The new influx of people and the unknown number of people who left the area in that 10 year period is the reason for the historical amnesia that obscures the past in South Dade.

Free’s son Wilbur settled in Oregon, married and raised a family, few of whom know much about their grandfather. His daughter Annie Vivian moved to Miami and married but apparently had no children. His son John U., III lived in Homestead all his life and had a family. Two of his daughters married into the Reinhart and Sizemore families but those families moved away from this area. A son, John U. Free, IV, also moved away. Today, other than the author, there are only a few people in South Dade who are familiar with the Free surname. This area has always had a very transient population which severely handicaps the ability of historians who are interested in writing about South Dade’s past. As a result, the few books which have been written about this area are filled with inaccuracies and unfortunately present a very restricted picture of the events that shaped the history of this area.

______________________________________________________________________

- 1850 U. S. Census of District 59, Meriwether County, GA, page 189, line 19

- 1900 U. S. Census of Atlanta Ward 2, Fulton County, GA

- 1910 U. S. census of Fulton County, Georgia

- Frederick & Butler was a surveying firm whose principals were John S. Frederick, who platted the Town of Homestead in 1904 and George O. Butler. It became “one of the most active engineering firms on the east coast,” according to the obituary published for John S. Frederick on page 1 of the February 26, 1910 issue of The Miami Metropolis

- Homestead Leader, March 6, 1924, p. 11

- Plat book 1, page 78, Miami-Dade County Clerk’s Office

- Miami Herald, May 26, 1911, p. 7

- Miami Metropolis, Oct. 13, 1914, p. 6

- Homestead Enterprise, Nov. 4, 1914, p. 4

- Miami Herald, May 26, 1911. p. 7

- Homestead Leader, March 6, 1924, p. 11

- The Weekly Miami Metropolis, May 31, 1912, p. 5

- Plat Book 1, page 9, Miami-Dade County Clerk’s Office

- South Florida Banner, December 6, 1912, p. 3

- South Florida Banner, February 28, 1913, p. 6

- Homestead Enterprise, July 15, 1915, p. 1

- Undated notice in the Ft. Lauderdale Sentinel, published in the Homestead Enterprise on July 20, 1916, p. 1

- South Florida Banner, June 27, 1913, p. 2

- South Florida Banner, November 21, 1913, p. 5

- Miami Metropolis, Oct. 13, 1914, p. 6

- Homestead Enterprise, August 6, 1914, p. 2

- Miami Metropolis, January 14, 1915, p. 8

- Homestead Enterprise, July 15, 1915, p. 1

- Homestead Enterprise, August 5, 1915, p. 3. Max Lehrman was the first documented Jewish businessman in Homestead. Weinburg and Meltzer were the second and third.

- Homestead Enterprise, January 30, 1916, p. 4

- Homestead Enterprise, November 23, 1916, p. 6

- Homestead Enterprise, March 13, 1919, p. 1

- Homestead Enterprise, January 8, 1920, p. 1

- Homestead EnterpriseOctober 13, 1921, p. 4

- Homestead Enterprise, November 16, 1922, p. 1

- Homestead Leader, November 18, 1926, p. 1

- Miami Herald, May 18, 1922, p. 9

- Miami Herald, November 18, 1921, p. 16

- Miami Metropolis, May 4, 1922, p. 9

- Homestead Enterprise, October 26, 1923, Section 2, p. 2

- Homestead Leader, June 14, 1923, p. 7

- Homestead Enterprise, July 20, 1923, p. 2

- Homestead Enterprise, March 13, 1925, p. 16

- Homestead Leader, April 9, 1925, p. 1

- Homestead Leader, April 2, 1925, p. 1

- Homestead Enterprise, April 3, 1925, p. 1

- Homestead Enterprise, April 10, 1925, p. 1

- Homestead Leader, April 16, 1925, p. 1

- Homestead Enterprise, February 27, 1925, p. 14

- Miami Herald, October 12, 1927, p. 7

- Homestead Leader, February 28, 1928, pp. 4-5

- Homestead Leader, July 21, 1928, p. 5

- Homestead Leader, August 9, 1928, p. 2

- Homestead Leader, October 25, 1928, p. 1

- Homestead Leader, November 13, 1928, p. 1

- Forgotten Heroes: Police Officers Killed in Dade County, 1895-1995, Dr. William Wilbanks, Turner Publishing Co., Paducah, KY, 1996, pp. 28-31

- , Miami Herald, November 24, 1923, p. 2

- Advertisement in the Homestead Enterprise, February 27, 1925, p. 2

That was lengthy and very interesting as well.

I really enjoy reading about history. I grew up in the Perrine-Cutler area. Later living in Homestead as a newlywed.

Wow, Jeff — What an interesting and well-researched article, as we have come to expect from your diligent work. I have two suggestions:

a. Link the Free properties to a map of downtown Homestead that shows where Free owned and built properties. The first map you showed was quite interesting. It would be nice to indicate on the maps which businesses were situated there.

b. The bit about the KKK is even more interesting. Suggest you work on a “History of the KKK in Homestead/Florida City.” It seems that we need to understand who were the members, when, and what actions the KKK took. If there were Black or Mexican-Americans impacted by the KKK, we should be aware of what happened. If there were pressures to join the KKK placed on members of the local community, we should also be aware of what happened to “enforce” compliance with or to join the KKK.

Much easier said than done, Frank. The business climate in Homestead in the early days was very dynamic and the information that has survived from that time period is very limited, so your suggestions, while good, are next to impossible to achieve. The subject of the KKK is exceedingly difficult to explore – no one wants to acknowledge that their ancestors belonged to that organization.

As always an interesting and amazing story of an early Homestead entrepreneur. How do you precipitate something out of nothing is magic and hard work. Thank heaven there are people like Mr. Free who can successfully practice this art. The world is full of idea people but not so many who can do the work to tame the wilderness and build a society. Thanks for all your work, Jeff.

11-9-2020

Hi Jeff, The preservation of our history will always be remembered through your efforts. Wonderful job here and the pictures are terrific!

Also, any connection between Joe Burton and our Burton Memorial United Methodist Church in Tavernier?

Yes, indeed. Burton was a prominent developer in the Tavernier area. Burton Dr., which leads to Harry Harris Park, is named for him.

Fine work, as usual, Jeff! Thanks for your diligent fact-finding.

What a fascinating article! My grandparents moved to Homestead from Georgia in 1919. They lived in a house which had been a post office on NW 3rd St. down from the First Methodist church on Krome Ave. I would love to see a picture of it! They were situated between two two story homes. My grandfather added two rooms in the back and a large porch in the front made of coral rock. The library was on the next street. The Livingstons lived across the street. Everything was destroyed in Hurricane Andrew.

Amazing Jeff. I can see the time and hard work you put into this article. Most would look at Homestead as just a town on the way to the Keys. Having married a beautiful young lady whose family had been there since the start I have heard bits and pieces of the history. Dottie Caves, Brenda’s aunt, was very active in the start of the museum. I learned a lot from her. Nothing stays the same. I guess that’s called progress. I find that with age I regret progress. I hunger for knowledge of the past. Maybe so I cannot see the demise. I truly respect your efforts to inform. I suspect because you have dug so deep in to those good old days you are not as greatly disgruntled as many of us that have long since been removed. We love you Jeff for what you do.