William S. Burkhart

By Jeff Blakley

Some people are gullible and there have always been men and women willing to take advantage of that. South Florida, starting in the early 1890s, became a fertile ground for hucksters to pursue their vocations. Convincing people to come to a place that never experienced frost, where you could get rich by growing fruits and vegetables without fertilizer or work other than digging holes for the plants and where every sick person would to be restored to glowing health simply by moving here was the story that was told by hundreds of promoters. William S. Burkhart was among them. His specialty was patent medicine, what today is called “alternative medicine” by those who recoil in fervent protest at being called quacks or purveyors of snake oil.

William Sherman Burkhart was born on April 6, 18621 in Hubbard Springs, Lee County, Virginia.2 His father, Noble C. Burkhart, was a farmer of very modest means, owning real estate worth $550 and having a personal estate of $300 in 1870.4 His son was educated in the local schools and attended Cumberland College5 in Rose Hill, also in Lee County.6 Cumberland College was more than a high school but less than a college. On January 1, 1889, he married Mary L. Dishman,7 the daughter of a shoemaker in Washington County, Virginia.8 At the time of his marriage, Burkhart was a “fruit agent,”9 what was later known as a commission man – the middleman between farmers and wholesalers. His wife died in 1922 of breast cancer and is buried in Spring Garden Cemetery in Cincinnati. Burkhart then married Lenora Schenk Forney on June 20, 1923. Lenora’s first husband, Stehman Forney, was a very well-known civil engineer who worked for the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey for over 50 years. He died in New York City in 1916.

Burkhart, who was not a medical doctor nor did he have any formal education in that field, took advantage of what has been termed the Golden Age of Patent Medicines.10 The social changes that occurred in this country after the Civil War, which included the rapid industrialization of the country, an increasingly urban population which lacked the herbal knowledge passed down by women for centuries, the lack of laws that would rein in purveyors of quack cures and the proliferation of newspapers and magazines as sources of information were all to the benefit of Burkhart and his fellow quacks. In the late 19th century and well into the 20th, he was known to millions, world-wide, for his patent medicine concoctions guaranteed to cure every ailment known to mankind. Today, no one other than his parents’ descendants know who he was.

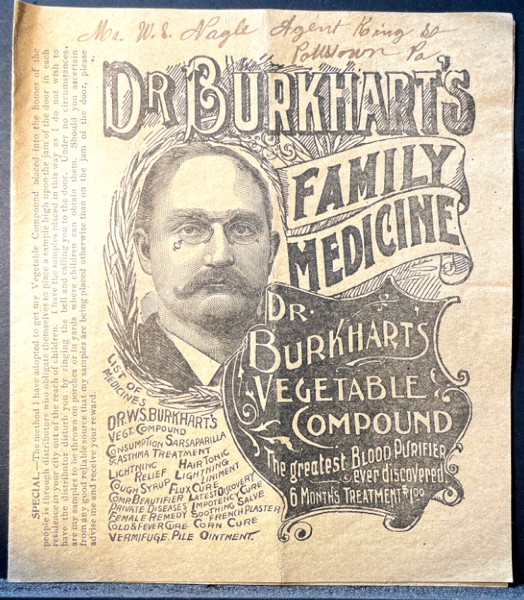

One of his most heavily advertised concoctions was Dr. Burkhart’s Vegetable Compound:

He sold many others, as shown in this page from a promotional pamphlet he sent to his sales women and men:

Patent medicines were so named because they were originally “manufactured under grants, or ‘patents of royal favor’, to those who provided medicine to the Royal Family” in England.12 The history of patent medicines, which are still sold today but under the name of alternative medicines, is quite interesting.

He introduced his Vegetable Compound on January 1, 189113 and went on to advertise his product nationwide.14 During this time, he also sailed to Europe semi-annually to attend to his factories in London, Paris and Germany.15 His sales amounted to half-a-million dollars a year.16

He first came to Miami to spend the winter in 1905.17 Here, he found a thriving market for his patent medicines that he guaranteed would restore anyone to vibrant health. Encouraged by what he saw as a bright future in the Magic City, he, like many others, invested in real estate.

His first purchase was of 90 acres between NW 22nd and 27th Avenues and NW 20th and 23rd Streets that he purchased in 1911. 15 acres of the property was a grapefruit grove and the balance was planted in tomatoes, beans and pineapples.18 In 1915, taking advantage of the appreciation in prices due to the growing population in Miami, he platted the land as Dr. W. S. Burkhart’s Winter Gardens subdivison.19

He then purchased 120 acres of high pineland near Claus Vihlen’s property in the Eureka area (in section 3-56-39), possibly from John Austin Hall, who claimed that land as a homestead in 1905 and patented it in 1908.20 Burkhart also purchased 60 acres in the adjoining section, 34-55-39. He called this property Morning View.21

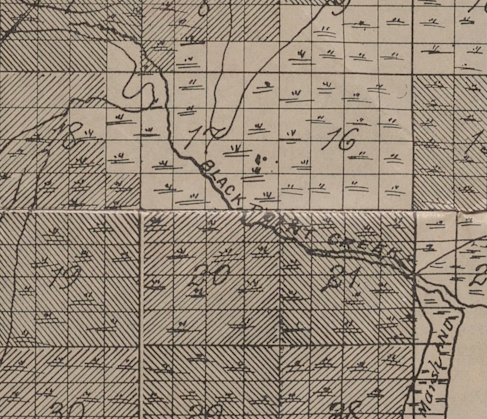

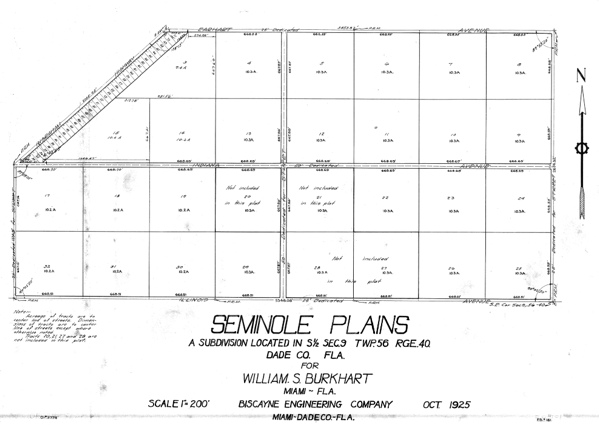

On February 17, 1911,22 he “purchased 1,160 acres of land along the north side of Black Point Creek”23 through the Richardson Investment Co.24 Seminole Plains, the name he gave to that purchase, was east of Old Cutler Rd., south of John H. Ehrehart’s holdings and north of Black Point Creek. On that land, Burkhart’s share croppers grew cabbage, beans, cucumber, egg plant, tomatoes, potatoes, sugar cane and other crops for the market, transporting them to the packing houses at Perrine via Franjo Road and the Ingraham Highway, also known as East Dixie. That road is now known as Old Cutler.

Before 1909, Dade County had built a wooden bridge across Black Point Creek as part of building what is now known as Old Cutler. It burned down and Dade County did not rebuild it until some time after the end of 1911, when Burkhart complained that the County had not rebuilt it, leading prospective growers to not rent his property.25

On the map above, Old Cutler Road crossed what was then Black Point Creek, before it was transformed into Black Creek Canal C- 1, just west of the number 1 where the number 17 (section 17-56-40) is shown.

After that bridge was rebuilt, Burkhart’s sharecroppers had additional options to sell their crops to commission men in Goulds for shipment north on the F. E. C. railway.

On June 30, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt reluctantly signed into law the Pure Food and Drug Act. That law was an almost word-for-word copy of a law passed in Indiana in 1899 as the result of the work of Harvey W. Wiley.26 As with all laws seeking to control powerful people, it took many years, until 1927, when the Food and Drug Administration was created, before the law resulted in making food and drugs safer for Americans. The passage of the law did not slow Burkhart down. From 1907 to 1925, he advertised even more heavily and in more states than he did from 1891 to 1906.27

In Miami, Burkhart applied the same sales techniques he had learned in promoting patent medicines to a new field: real estate, farm land and agricultural products. He fed the press a steady diet of claims that raise the eyebrows of those who read them now. Among them:

In November of 1912, Burkhart touted the high quality of the sugar cane he was growing at Seminole Plains, claiming that it was superior to that being imported from Cuba. Because of the quality, he announced plans to plant 1,000 acres of his land in sugar cane and build “a sugar mill to grind the output.”28 By October of the next year, Burkhart announced plans to plant 1,700 acres in sugar cane but admitted that only 60 acres had been planted.29

In 1913, he announced the formation of the Cooperative Plantation & Sales Co., managed by B. C. Jenkins, of Cincinnati. It would be formed to market the syrup produced from his sugar cane.30 A search on “B. C. Jenkins” in Cincinnati from 1900 to 1930 failed to return any hits.

In early 1914, he stated that “practically every store in the county has agreed to install Seminole Plains Syrup as its leading brand.”31

In late 1914, he said he was going to plant 1,200 acres in tomatoes, three times as much acreage as Tom Peters and one-quarter of the total acreage planted in the Homestead District that year.32

The Cooperative Plantation & Sales Co., which Burkhart claimed to have established in 1913, never incorporated, so in 1916, he announced the formation of the Cooperative Fruit & Vegetable Club, with Burkhart as president and E. H. Threadgill as secretary and treasurer. Allegedly, 80% of the stock was subscribed to, mostly by northern capital.33 No records were found for the Letters Patent for either one of these organizations.

In 1927, Burkhart started to grow papaya, which took off in popularity in 1928. Improved varieties of the plant were offered by the Sub Tropical Experiment Station on Brickell Avenue in Miami as early as 1913.34

He was one of many who grew papayas in Dade County. Burkhart said he built a factory capable of producing 10,000 pounds of papaya marmalade and crystallized papaya candy every day. That is 10,000 pounds of each product.35 In 1929, he stated that papaya syrup was “supplanting maple syrup for buckwheat cakes” in New England.36 However, he did have a store in downtown Miami, at 31 N.E. 1st Street, where some of his syrup, marmalade and candy was sold.37

In 1928, he claimed to have spent $100,000 ($3,107,788 in 2023 dollars) improving Seminole Plains in the previous year.38

His 180-acre papaya plantation was “protected by a six-foot dike constructed eight months ago” and had a pump capable of removing 500,000 gallons of water an hour. … Blocks two acres long and one acre wide checkerboard the plot and roads surround the blocks. Underlying strata of rock prevent the moisture of the four-foot deep soil from escaping. … In figuring out how to make the “papaya grow larger that it had heretofore been known to do in Florida,” he “hit upon the idea of blended soil. … Fortunately, he [had] every kind of soil needed on his own acres. He carries what he calls black diamond from the southeast corner of the plantation to blend with glade and marl; he brings red soil from his farm in Redlands to add to that and then he puts in some compost.”39

Burkhart was a consummate marketing person. After reading many newspaper accounts of his accomplishments, it is very difficult to accept much of it as truth. An accurate account of Burkhart’s activities, at any time, is difficult to determine solely by reading newspaper accounts about him. Almost all of the information in the newspaper articles reads like an advertisement, not objective reporting. Every statement of “fact” in those articles came from Burkhart. In none of the articles was any agricultural figure, well-known or not so well-known, mentioned. Dr. Johann Peterson, another quack who owned Bonita Grove on Hainlin Mill Dr., never mentioned Burkhart as a competitor – both grew papayas and both touted its health benefits.

In 1923, he put about 290 acres of his property on the market as the Seminole Plains subdivision to take advantage of the appreciation in real estate prices. He kept the balance of the property, farming potatoes and papayas.

In about 1925, he established Royal Palm Gardens on a portion of his Seminole Plains property. By 1928, he said he had “100,000 small palms growing in lines as straight as an arrow and one mile long, beginning away back at the highway.” He also had a house on the property, “a creamy yellow cottage, built on the lines of the East Indian structure that is the parent of our American bungalow.” The house was located next to the East Dixie Highway and was adjacent to a slat house covering over two acres with another 450,000 palm trees. When he “finished planting his baby palms, there will be 500,000 in the gardens,” he told a reporter for the Miami Herald.41

The newspapers reported that he owned anywhere from 1,000 to 2,500 acres of land, depending on what initiative he was promoting at the time the article was published. Tax delinquency lists published in 1929 show that he or family members owned at least 589 acres in sections 9, 16 and 17 of township 56 south, range 40 east.42 The holdings of the Campo Rico Farms were south and west of Burkhart’s holdings.

Burkhart had two children: Mary Mabel and William Shearman, born in 1896 and 1900 respectively. William S. continued to live in South Dade until at least 1935, when he and his family, who lived on Cadima Avenue in Coral Gables in 1940, told the enumerator they had lived in Goulds in 1935. His occupation in 1940 was as a “vegetable grower.”43 Burkhart cultivated potatoes on the family land and kept meticulous records, according to an article in the Miami Herald in 1936.44 By 1950, William and his family had moved to Ft. Lauderdale, where he became a real estate salesman.45 William’s children, Beverly and William, lived in the Orlando area and his son-in-law, James W. Olgivie, Jr., was a biochemistry professor at Johns Hopkins and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.46 Mary Mabel married Nobel Gildersleeve in 1918 and they lived in Philadelphia, where Gildersleeve was a wealthy executive of a ship-building company. They wintered in Miami Beach, where Noble was enumerated in the 1930 census as living in a house worth $30,000, a substantial sum at that time. His occupation was given as “stock broker.” Mabel died in 1962 and her husband in 1964. Both are buried in Portland, Connecticut.

In 1933, Burkhart furnished Dade County with free Canary Island Date Palms to landscape Franjo Rd.49 In another article that same year, he had a total of 50,000 Canary Island Date, Queen, Washingtonia, and Royal Palms,”in some directions extending in rows almost a mile long.”50

W. S. Burkhart rose from humble beginnings in the hills of Southwest Virginia, the eldest of 11 children, to a fortune unimaginable to his siblings and died at his home in Reading, Ohio, a suburb of Cincinnati, on November 13, 1941. No trace remains of his sojourn in Dade County and not much more in Cincinnati. He is buried beside his first wife in the Spring Grove Cemetery.

His property here was sold off after his death. Some of it was purchased by G. Walter Peterson, a big potato grower in Goulds, and August Burrichter, another potato grower who lived in Homestead. John W. Campbell, another big grower in Goulds, probably purchased some of Burkhart’s property also. Once those sales were completed and his son had moved out of the area, the very wealthy man whose fortune was built on self-promotion and real estate speculation was quickly forgotten.

In my article about Franjo Road, I mentioned Burkhart at the end of the article. That is because Burkhart’s land adjoined John H. Ehrehart’s property. A substantial part of the Lakes By the Bay subdivision was built on land formerly owned by Burkhart.

This article is part of a series about the history of the land east of U. S. 1 from Cutler down to Florida City, a part of the history of South Dade that has not been addressed in print to the best of my knowledge.

______________________________________________________________________

- Social Security Death Index

- Find A Grave memorial #69878999: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/69878999/william-sherman-burkhart

- 1870 census of White Shoals, Lee County, VA3 Lee County is in Southwest Virginia and borders Harlan County, KY and Claiborne and Hancock Counties in TN.

- Obituary in The Post, Big Stone Gap, Virginia, Nov. 20, 1941, p. 5

- Topographical map of Lee County, VA from the Library of Congress

- Virginia marriage records, available on Ancestry.com

- 1880 census of Washington Co., VA, for John D. Dishman.

- Virginia marriage registers, available on Ancestry.com

- Smithsonian Institution Patent Medicine Collection

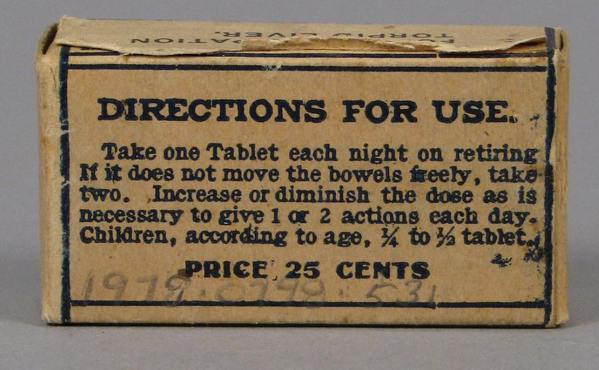

- Catalog # 1979.0798.531, from this website: https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1282261

- https://www.hagley.org/research/digital-exhibits/history-patent-medicine

- The Cincinnati Post, January 2, 1906, p. 5

- A search on newspapers.com for “W. S. Burkhart” in the United States from 1891 to 1906 returned 1,058 hits in 28 states. Notably, Florida was not one of those states.

- The Cincinnati Post, January 2, 1906, p. 5

- The Post, Big Stone Gap, Virginia, Nov. 20, 1941, p. 5. His factories were in Cincinnati, Ohio; London, Paris and Berlin, Germany but no year was given for that sales figure.

- Miami Metropolis, Nov. 10, 1921, p. 13

- Miami Metropolis, Dec. 28, 1911, p. 1

- Plat Book 2, p. 104. See also Plat Book 5, p. 22

- The land, in 3-56-39, was initially claimed in 1897 by Robert H. Hagen, but his claim was cancelled in 7 months. It was then claimed in 1898 by Oscar L. Johns, whose claim was cancelled in 1904.

- Delinquent tax lists from 1940 enabled the author to locate these parcels of land.

- Miami Metropolis, February 18, 1911, p. 1

- Miami Metropolis, March 22, 1911, p. 1

- Miami Herald, February 18, 1911, p. 1

- Miami Metropolis, December 28, 1911, p. 1

- The Indianapolis Star, February 7, 1982, Section 2, pp. 26-27

- A search on newspapers.com for “W. S. Burkhart” from 1907 to 1925 returned 1,492 hits in 42 states, including 364 in Florida.

- Miami Herald, Nov. 27, 1912, p. 8.

- Miami Metropolis, October 10, 1913, p. 2

- Ibid.

- Miami Herald, Feb. 7, 1914, p. 1. Research failed to find any evidence to support that claim.

- Miami Metropolis, Nov. 3, 1914, p. 1

- Miami Metropolis, January 5, 1916, p. 8. E. H. Threadgill ran an advertisement in the Miami Metropolis on April 1, 1915, p. 7 that read: BETTER BARGAINS IN REAL ESTATE with an address of 206 12th St., the Halcyon Building. Burkhart often stayed at the Halcyon Hotel.

- Miami Herald, Womans Club Edition, August 7, 1913, p. 31 (15)

- Miami Herald, Oct. 7, 1928, p. 28

- Miami Daily News, January 6, 1929, p. 36

- Miami Daily News, Dec. 16, 1928, p. 24

- Miami Herald, January 1, 1928, p. 21

- ibid

- plat book 20, page 42

- Ibid.

- Miami Daily News, July 1, 1929, p. 21

- 1940 U. S. census of Coral Gables

- Miami Herald, March 19, 1936, p. 29

- 1950 U. S. census of Ft. Lauderdale, Broward, FL

- Obituary for James W. Olgivie, Jr., The Orlando Sentinel, April 14, 2003

- Miami Daily News, June 11, 1933, p. 247

As late as 1937, he had 10,000 Canary Island Date Palms, 5,000 Mexican Fan Palms, and “great numbers” of Pandanus, Kentia, Areca and other palms on his property.48Miami Daily News, May 2, 1937, p. 16 - Miami Daily News, August 8, 1937, p. 24

Interesting article about the characters who inhabited and had a substantial influence on South Dade. Thanks for documenting facts about this person and his effects on the region.

Wonderful.

Another fine job, Jeff. Thanks for making the time. I’m wondering if there is a convenient source — USDA, Florida Department of Agriculure, local records — that would indicate the annual cultivation of various crops in Dade County by acreage and yield (tons or bushels). I’ve always thought that tomatoes dominated farming in South Dade, but your articles have revealed a much greater variety of crops. Sounds like some earlier farmers were experimenting with lotsa stuff (e.g., papayas) but eventually zeroed in on the things that were most in demand and most profitable.

Thanks Jeff for another informative look into our history here. Although being born and raised here, there is a lot of history of our area that I don’t know. As for you Edison McIntyre we may know each other. I graduated South Dade High in 1969. Edison, what about you?

Fantastic and comprehensive work, wow!