by Jeff Blakley

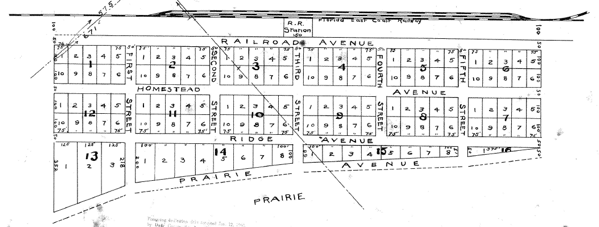

The Town of Homestead, which was surveyed and platted by J. S. Frederick, C. E.,1 in June, 1904, was the next to the last community created by the arrival of the Florida East Coast Railway on mainland Florida. Incorporated in 1913, it is the second-oldest municipality in what is now Miami-Dade County. The last community, originally known as Detroit, incorporated in 1914, is the third-oldest municipality in the county. When Frederick platted the Town of Homestead, Miami-Dade County (known as Dade County until November 13, 1997) covered the area from Stuart south to just below Lake Surprise.

John Stanley Frederick was born on June 24, 1853 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,2 the son of Thomas E. and Martha June Gilbert Frederick. John’s father was a merchant of quite modest means. In 1860, he had a real and personal estate of $2,000 which by 1870 had decreased to just $1,800. One of four children, John had a sister, Alice M. and a brother, William C. Another sister, Susan, born in 1851, apparently died between 1860 and 1870. The family moved around quite a bit: in October of 1850, shortly after his marriage to Martha on June 20 in Cuyahoga County, OH, Thomas, a merchant, was about 70 miles away, staying in a hotel in Centre Township, Columbiana County, OH. In 1860, he was in Champaign County, IL and in 1870, he was in Cumberland County, NJ. By 1880, he had moved to Baltimore, an independent city in Baltimore County, MD.3

Nothing is known about John’s education but in May of 1876, at the young age of 23, he was admitted to the bar in Baltimore, Maryland. From then until 1889, he practiced law, was active in civic affairs and sold real estate there.4

On September 6, 1883, he married Antoinette Elizabeth Gazzam in Utica, NY.5 The Gazzam family was very prominent in Pittsburg, PA and in Utica, NY. Antoinette’s father, Audley William, was a lawyer who specialized in bankruptcy. Antoinette had 3 sisters and one brother: Mary Van Deusen, Edwin Van Deusen, Irene Gilbert and Maria Florence. In late 1889, John and his wife, their two children, Edwin Stanley and Florence Antoinette, and his sister-in-law, Maria Florence, moved to Cartersville, Georgia.6 He may have continued practicing law there. Two more children were born to John and Antoinette in Cartersville: Thomas Emanuel on December 17, 1890 and Audley William, on March 16, 1894.7

As the construction of the F.E.C. Railway made its way down the coast, thousands of merchants, laborers and professionals of all kinds, including engineers, moved to Florida to improve their families’ prospects. John Frederick may have been one of them. It is unknown when he and his family left Cartersville to journey to Dade County, but it probably wasn’t before the spring of 1895, as Audley William was just an infant then.

Eugene Dearborn may have been another. He was born on June 5, 1859 in Mason County, IL.8 In the mid-1880s, the Dearborns lived in Wayne, NE, where Eugene taught school and worked for a railroad company.9 The F.E.C. Railway reached Titusville in February, 189310 and on August 14, 1893, the Dearborns’ daughter, Dora, was born there.11 It is possible that Dearborn worked for the F.E.C. Railway. By early 1894, the family had moved to Cocoanut Grove, where Eugene Dearborn’s father, Marcellus, purchased the SE 1/4 of 10-54-41 on July 24, 1894.12

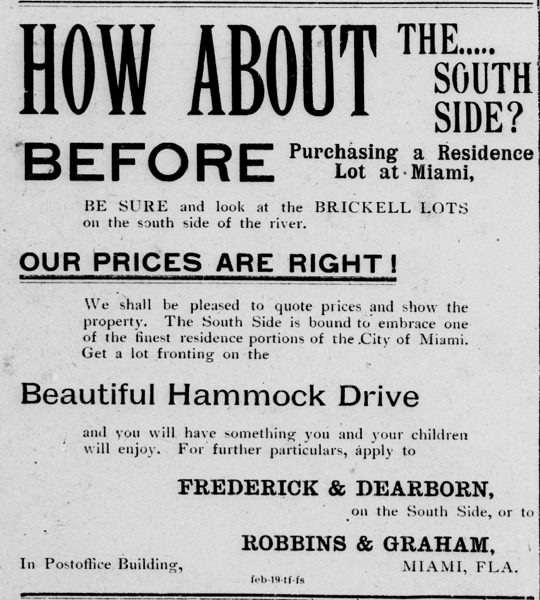

Frederick’s first residence was in Cocoanut Grove,13 where he and Eugene C. Dearborn entered into a partnership, Frederick & Dearborn, selling real estate. They placed their first advertisement, stating that they were the “authorized agent for the sale of the Brickell (South Side) lots, the most desirable residence portion of Miami,” on June 5, 1896.14 Their “well-equipped office” was on 18th St., south of the Miami River, east of Avenue D.15

By early 1897, John had moved his family to 20th St. and Avenue D, then known as Southside.17 His house, “The Wayside Cottage,” was located 2 blocks south of the Miami River.18

In May of 1897, the Dearborns moved into their new 11-room stone home in Cocoanut Grove, erected on 3 acres near the residences of the Trapps and W. W. Culbertson.19 In July of that year, he offered it for sale or exchange, along with the 160 acre homestead purchased by his father, Marcellus, one mile north of his house.20 In 1900, he had it subdivided into 16 ten-acre lots.21 Shenandoah Middle School is located on a portion of that property.

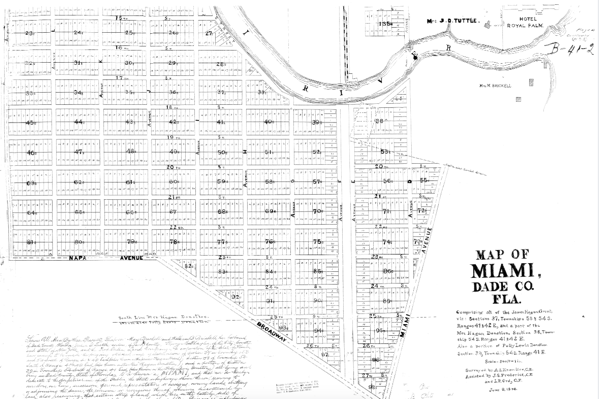

By July of 1897, Frederick and Dearborn had parted.22 That was likely because Frederick was very busy with surveying jobs. How John Frederick made the transition from being a lawyer to a civil engineer is unknown but he may have learned the fundamentals from Abner L. Knowlton, who surveyed the town of West Palm Beach in 1893,23 the Town of Ft. Lauderdale in 1895,24 and the City of Miami in 1896.25 John S. Frederick and Lewis R. Ord assisted Knowlton on the latter survey.

Knowlton was an experienced civil engineer who was born in New Hampshire in 1818, served the North in the Civil War and did surveying work for the Northern Pacific Railroad in Washington state before coming to Jacksonville after 1891.26 The plat of the town of Fort Lauderdale was ordered by William and Mary Brickell while the plat of the City of Miami was ordered by William and Mary Brickell, Julia D. Tuttle, Henry M. Flagler and the Ft. Dallas Land Co. in cooperation with the State of Florida.27 28 Both of these projects covered a lot of area and Knowlton had his two assistants to help him. No doubt, there were many more rodmen, chainmen and transitmen working on these jobs but their names have been lost to history.

After Frederick completed his work with Knowlton in early 1896, he embarked on his new career as a civil engineer. In June of 1897, he had “a large contract for surveying certain land owned by Julia D. Tuttle at New River, at which place he has a camp and a force of men and a large houseboat.”29 By the end of 1897, Frederick had completed four large jobs and had also completed the work necessary to move the route of the road from Miami to Coconut Grove some distance west to get it off the property of William Fuzzard. Fuzzard had posted notice in July that effective Sept. 1, the road, which ran through his property, would be closed to public travel.30 Frederick’s surveying work was in lieu of a monetary donation to the cost of building the road, to which fifty-six individuals and companies, along with the Dade County Commission, had contributed.31

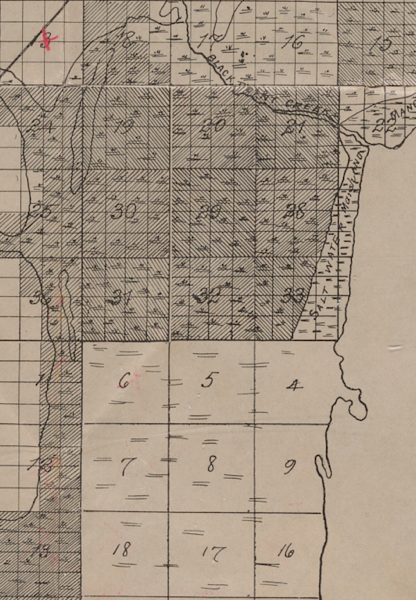

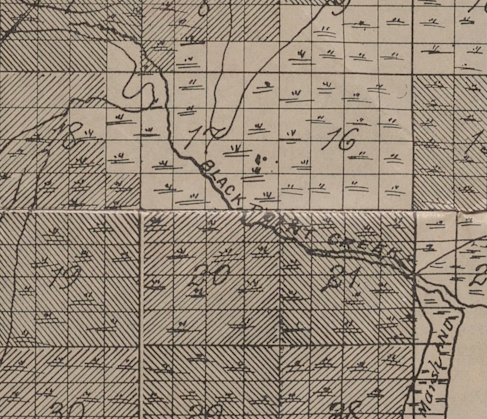

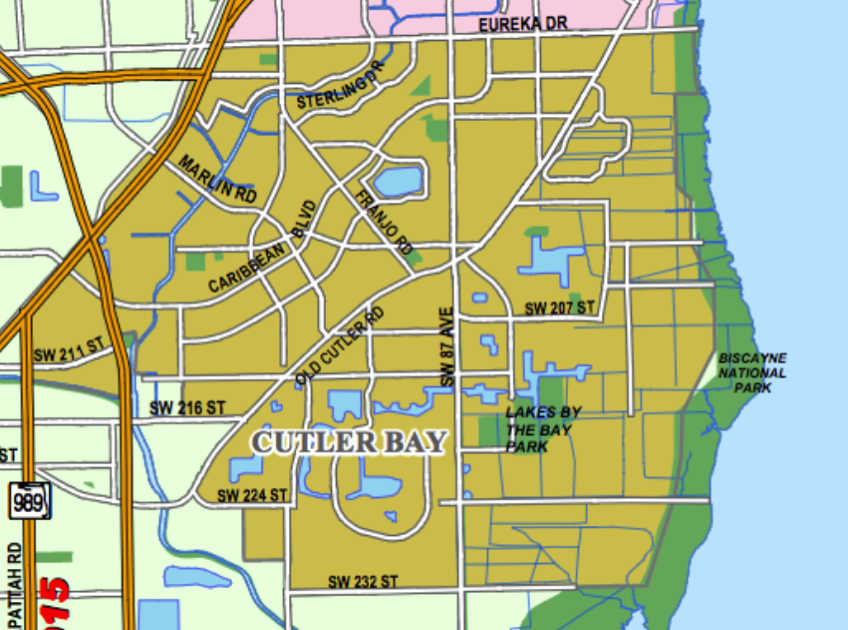

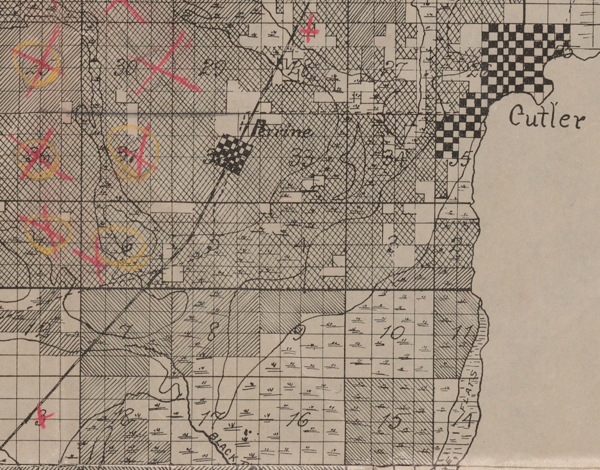

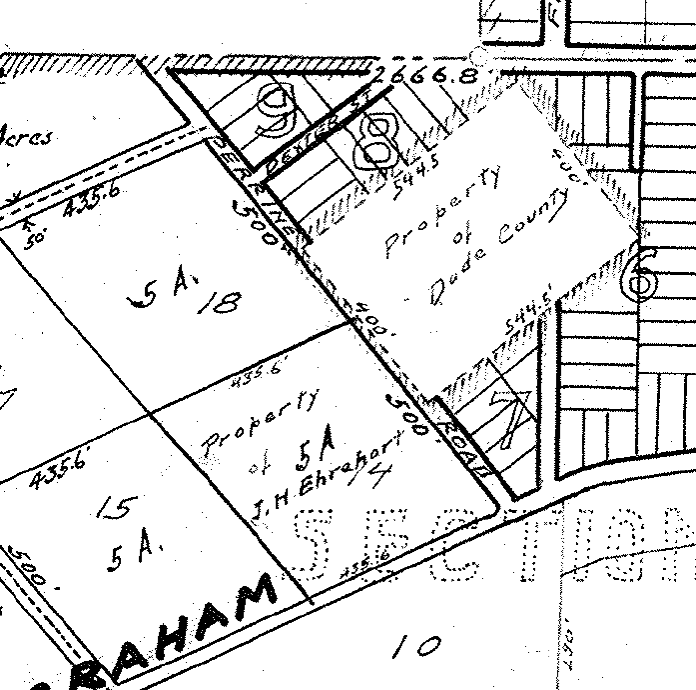

In 1898, he was elected as alderman for the City of Miami32 and was also appointed Deputy U. S. Engineer and tasked with surveying the Ragged Keys, which are a few miles north of the northern tip of Key Largo.33 Starting in June of 1899, he subdivided about 1,000 acres of land northwest of the Little River area into 10-acre tracts for the Land Department of F.E.C. Railroad.34 In August, he went to Cutler “to finish sub-dividing into 10-acre tracts certain lands of the Perrine Grant, which work was commenced some 30 days since.”35

John Frederick filed a claim for the SW corner of Bauer Dr. and Richard Rd. on August 5, 1902 and relinquished it on April 5, 1904. His sister-in-law, Maria Florence Gazzam, claimed her homestead at the NW corner of Waldin Dr. and Richard Rd., adjacent to John’s claim, on the same day as her brother-in-law. She patented her claim on December 3, 1905, shortly after marrying George W. Kosel in August of that year. George had claimed the NW corner of Redland Rd. and Plummer Dr. in July of 1902.

Junius T. Wigginton claimed a homestead at the southeast corner of Bauer and Redland on July 17, 1904. He married Frederick’s daughter, Florence, in Lexington, KY on November 30, 1905.36 His claim was one mile east of the claim of his wife’s aunt, Alice Frederick, who had married Harry LeForest Hill.37 Alice and John’s mother, Martha G. Frederick, died at Alice’s home on December 31, 1910.38 Alice went on to marry Erich B. Grutzbach, another pioneer in the Redlands, who claimed a homestead in 1908 at the NW corner of Bauer and SW 207th Ave, one mile west of Alice’s claim. They were married in 1911 in Buena Vista.39

In late June of 1902, John Frederick was hired by the F.E.C. to do a survey of the lands south of the Miami River and supervised a large crew of men which worked until early September.40 Frederick then went to St. Augustine to discuss his work with Joseph R. Parrott, who was the vice-president and general counsel of the railroad. After their meeting, Frederick, who was “very glad the first work through the Everglades [was] finished,” returned to Miami and began working on the “surveying work which had piled up enormously during his absence.”41

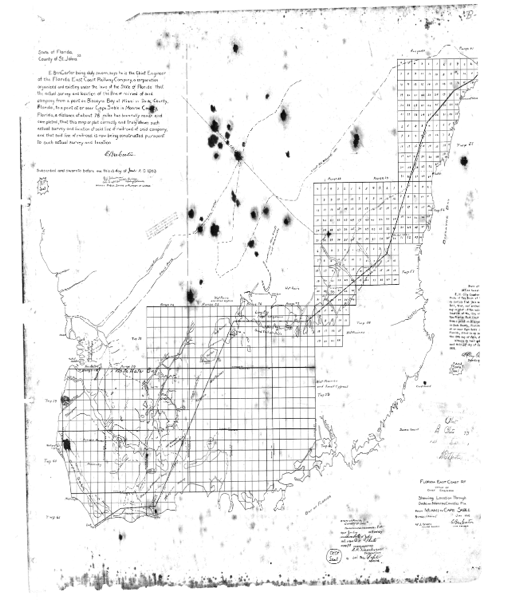

That the F.E.C. had planned to continue past Miami is evident by studying the plat of the City of Miami, started by Knowlton with the assistance of John S. Frederick and Lewis R. Ord in late 1895. The survey, which reserved land for the continuation of the railway south of the Miami River between Avenues E and F, is evidence of those plans.42 Frederick’s report was discussed at the next meeting of the Board of Directors43 and the decision was made to advertise for someone to continue the survey that Frederick had started. William J. Krome was hired and he began his Cape Sable Exploration Survey on October 5, 1902.44 and completed it on May 31, 1903.45 Krome submitted his survey to the Clerk of Courts of Dade County in June of 1903 and it was filed for record on July 8, 1903.

In November, James E. Ingraham, the 3rd vice-president of the F.E.C., made a trip to South Dade to look over the country and make further plans after Krome’s report had been reviewed. He was accompanied on his tour by William J. Krome, John S. Frederick, Fred S. Morse, who was the land agent for the Model Land Co., and Edward A. Graham,46 who was the captain of Ingraham’s yacht, the Enterprise,47 and a photographer. This is a photograph, taken by Graham, of the party on their way to Paradise Key, which would become Royal Palm State Park in 1916:

Ingraham selected 600 acres of land in section 13, township 56 (sic – 57), range 38 to be used by the F.E.C. for buildings, yards and other terminal purposes.48

“Other terminal purposes” included a town, which came to be named Homestead and which was surveyed and platted by John S. Frederick. After completing that work, Frederick returned to Miami to work on the many surveying jobs he was being asked to do. By 1904, he had so much work that he hired his son, Edwin Stanley “Ted” Frederick, to help him.49 By 1906, with his business continuing to grow, John entered into a partnership with Clarence L. Barclay, who came down from Johnstown, PA in November. Frederick renamed his business Frederick & Barclay50 but unfortunately, that partnership did not last long, for Barclay left and went back to Johnstown the following March.51

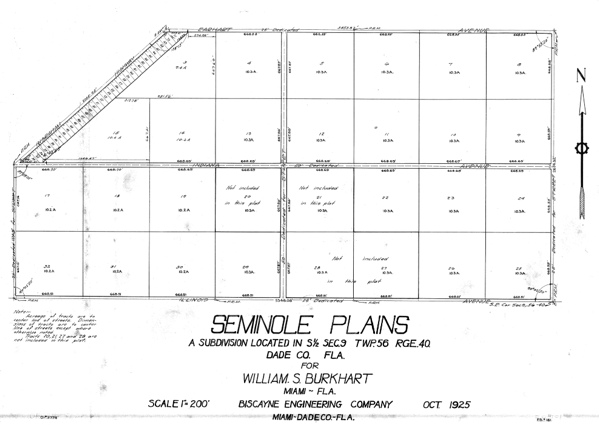

John S., E. S., or both created 43 out of the 166 plats in Book B, which is just over 25% of the total. In 1909, E. S. Frederick formed a partnership with George O. Butler and the firm, Butler & Frederick,52 became “one of the most active engineering firms on the east coast,” according to John’s obituary.53 Butler was a surveyor and politician who is known as the father of Palm Beach County.54

John S. Frederick died on February 26, 1910 at the age of 53. He came down with a bad cold as a result of wading in waist-deep water while on a job near Ft. Pierce. That developed into pleurisy which resulted in his death. His widow, who had moved to Moore Haven to be near her sons Ted and Audley, died in 1922 in Daytona. Both are buried in the Miami City Cemetery.

______________________________________________________________________