Homestead’s First Postmaster

By Jeff Blakley

Shortly after I published David Torcise’s Google Earth map of the locations of the homesteads of early settlers in this area, I received an e-mail from a man who thanked David and me for our work and stated that it had helped him clarify some issues about his ancestor. While looking at the names on homesteads in his ancestor’s area, I noticed the name “Berte A. Parlin,” who had claimed 80 acres on either side of Krome Avenue from Avocado Drive down to King’s Highway. “What an odd name,” I thought, and so I decided to do some research into who this person was.

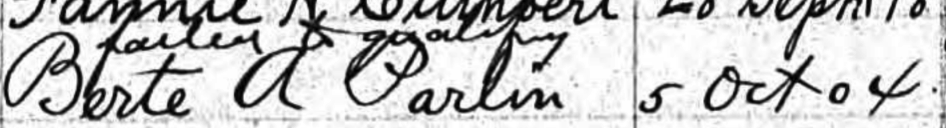

A search of Ancestry.com, using the words “Berte Parlin” in the search engine, brought up an entry that said “U.S., Appointments of U.S. Postmasters, 1832-1971”. That caught my attention because I had always thought that W. D. Horne was appointed as Homestead’s first postmaster. It turns out that he wasn’t – Berte A. Parlin was. Parlin was appointed postmaster on October 5, 1904 and W.D. Horne was appointed on January 23, 1905.

As I researched Berte Parlin further, I discovered some very interesting information, which I will share with you in this post.

Berte A. Parlin was born in January, 1862 in Charleston, Orleans County, Vermont, the son of Daniel Owens Parlin and his wife, Lucina Pierce Parlin. He had a brother, Henry W., born about 1856; a sister Lizzie A., born about 1858; another brother, Fred L., born about 1860; and another sister, Anna P., born about 1865. Berte’s father was a farmer and Berte appears in the 1880 census, living with his parents and working on the farm. In 1890, however, he lived at 559 Adams in Dorchester, Massachusetts, which had been founded by the Puritans in 1630 and had been annexed by Boston in 1870. Berte’s occupation was listed as “civil engineer.” In 1892, he was admitted to the Boston Society of Civil Engineers and he lived in Dorchester until at least 1897. During the Spanish-American War, Berte was a sergeant in Company K of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Engineers. After the war was over, Berte went back to Vermont, where he was enumerated in the 1900 census as living with his mother and sister, Lucina and Lizzie, in West Charleston. His occupation was listed as “civil engineer.”

David Torcise, who is also a very curious man, looked for a Parlin genealogy on Google Books and found The Parlin Genealogy: The Descendants of Nicholas Parlin of Cambridge, Mass. It was compiled by Frank Edson Parlin, A.M., PhD. in Cambridge, MA in 1913. There, I read that in 1902 Berte Parlin had “entered the employ of the Florida East Coast Railway Company and was Resident Engineer on the construction of Long Key Viaduct.” That piece of information really intrigued me, because I have never known much about pre-1904 Homestead.

While reading Jerry Wilkinson’s account of William J. Krome’s survey expedition of 1902-1903 to Cape Sable, I noted a letter dated October 20, 2 (presumably 1902 since the previous letter was dated October 13, 1902) that mentioned Parlin. He had been part of Krome’s survey team for the Cutler Extension, which was what the portion of the railroad from Miami to Homestead was known as since Homestead did not yet exist.

A reconstructed time-line for Berte A. Parlin would seem to indicate that he had started working for William J. Krome, who was in charge of the survey for the Cutler Extension, at some time in 1902. Krome started his expedition to Cape Sable in December, 1902 but I’ve uncovered no documentation that mentions Parlin as being part of Krome’s Cape Sable Expedition. Without a time-line for the completion of the Cutler Extension survey, it is difficult to tell how Parlin came to file his claim for his homestead in 12-57-38 and 7-57-39 on October 22, 1903. That homestead was for 80 acres on each side of Krome Avenue (a township line, which was more important for future roads than a section line) from Avocado Drive down to King’s Highway.

Entries in William J. Krome’s 1904 diary, a copy of which was kindly furnished to me by Jerry Wilkinson, make frequent mention of Parlin in the first half of 1904. At that time, Parlin occupied an office in Miami, where he apparently worked in some capacity for the FEC. In his diary entry for July 7, 1904, Krome wrote that Parlin “is out of a job now and going down on his homestead to live.” On July 18, Krome met with Parlin and Dan Roberts on Krome’s homestead, a short distance away from Parlin’s homestead. Dan was clearing Krome’s property and setting out fruit trees.

Parlin was appointed postmaster of Homestead on October 5, 1904. How that came about is hard to tell, but it didn’t hurt that he worked for Flagler and no doubt had connections in high places. On November 30, William Krome made a trip to his homestead, putting up his horse at Parlin’s house, a short distance away. But the entry for December 30, 1904 states that he spent the evening with Parlin at his office in Miami, so it appears that Parlin was once again working for the FEC. No doubt, his re-employment by the FEC impacted his ability to carry out the duties of a postmaster, which likely explains why the entry in the appointment book reads “failed to qualify.”

The tiny handwriting, sandwiched between Parlin and the entry for Fannie A. Cuthbert above indicates that it was written after the other entries.

William D. Horne was appointed postmaster in Homestead on January 23, 1905, taking the place of Berte A. Parlin, who likely was busily working on some part of the Key West Extension construction project. The mail between Miami and the post offices at Coconut Grove, Larkins, Cutler, Perrine, Black Point and Homestead began to be carried by the F.E.C. Railway on July 17, 1905.1 Prior to that, mail had been carried to these post offices by contractors. Was there a contractor who brought the mail to Homestead? No record of Parlin being a contractor to carry mail has been found so who brought the mail to Homestead prior to it being transported by the railroad in the summer of 1905 is not known. Parlin’s homestead was near Krome Avenue and Avocado, not close to the route of the railroad so when Horne arrived in Homestead late in 1904 and established his business next to the railroad tracks, he was a great candidate to be the next postmaster in town. Despite the fact that Berte Parlin was not confirmed, he, not W. D. Horne, was the first appointed postmaster in Homestead.

Further documentation on Parlin’s role in the construction of the Key West Extension has not yet surfaced, so there is a gap in our understanding of Parlin’s life between December 30, 1904 and his death on October 18, 1906.

An article, Building the Overseas Railway to Key West, by Carlton J. Corliss, which appeared in Tequesta in 1953, gives a long list of engineers who worked under Chief Engineers Joseph Meredith and William Krome. The list includes B. A. Parlin. That confirms the Parlin genealogy account of Parlin being the Resident Engineer at Long Key.

Corliss wrote that “construction commenced from Homestead southward in the summer of 1905” on the Key West Extension. Jerry Wilkinson provided further detail in his article, saying that construction of what later became known as the “Eighteen Mile Stretch” south of Florida City commenced in April of 1905.

According to Corliss, the Long Key Viaduct “consisted originally of 180 fifty-foot arches, to which 42 35-ft. arches were added before the road was opened, bringing its total length up to 11,958 ft., or 2.15 miles.” Construction of the viaduct could not start until barge-mounted concrete mixers were built and in place. That happened by early July, 1906, according to an unidentified clipping dated June 27, 1906 in the archives of the Flagler Museum in West Palm Beach. By early October, according to Dan Gallagher in his book, Florida’s Great Ocean Railway, “the first 13 piers at the east end of the Long Key Viaduct were complete but had no arches.” For those interested in how the Key West Extension was built, Gallagher’s book is an indispensable resource.

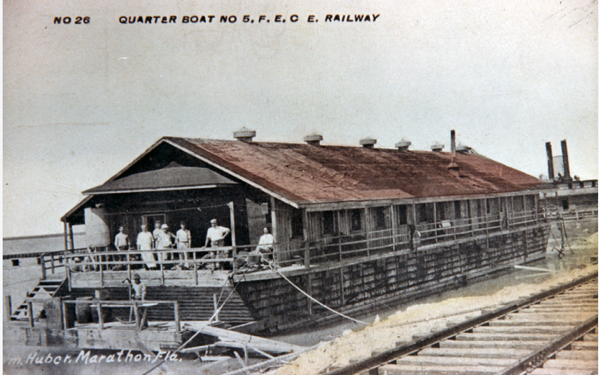

The Parlin genealogy, cited earlier, stated that “[o]n October 18, 1906, the quarterboat upon which he [Parlin] had his headquarters was carried out to sea during a West Indian hurricane, Mr. Parlin and about one hundred forty-five employees being on board, of whom over half lost their lives.

Courtesy of the Monroe County Library

From accounts given by survivors, Mr. Parlin was crushed in the collapse of the boat when it broke to pieces on the outside reef. Les Standiford, in his excellent account of the Key West Extension, Last Train to Paradise, wrote that Parlin “rushed below to warn the men who had taken refuge in the shallow hold. Before he could get a word out, a huge support fell and crushed him.” Researching further, I found two accounts of what happened to Quarterboat #4 when the 1906 hurricane hit Long Key. Both were written by survivors of the storm. William H. Saunders, who was probably related to Chesley Saunders, the husband of Marie King (daughter of William King), authored a long account, The Wreck of Houseboat No. 4 October 1906, for Tequesta in 1959. He wrote that “the Division Engineer and his men,” which would include Parlin and his assistants, lived in a one-story frame house that had been built on the deck of the barge. The storm hit early in the morning of October 18, 1906 and the mooring cables of the houseboat broke at about 7:30 a.m. and it started drifting southeast towards the Gulf Stream. At about 9:00 a.m., the frame house “blew away like a pack of cards, carrying an unknown number of men with it.”

William P. Dusenbury, another engineer who was aboard the houseboat, wrote his account for the Tampa Morning Tribune on October 26, 1906. Here is an excerpt:

“W. P. Dusenbury, of St. Petersburg, the civil engineer who was in charge of the concrete pier work at Long Key on the Florida East Coast extension railway at the time of the hurricane, was registered at the Hillsboro hotel last night. Mr. Dusenbury was the first man picked up of those who were set adrift by the hurricane at Long Key. With 48 others, he was rescued 12 miles from the Bahama rocks, on the Bahama banks. He was the first man picked up and was the first man of those adrift to land at Key West after the storm.”

Dusenbury wrote that the houseboat broke loose from its moorings at 5 a.m. and that “[o]ne hour after reaching the Gulf Stream, with seas breaking over her 50 to 60 feet high and combing in water of 900 fathoms, the craft was beaten to pieces.”

Both Dusenbury and Saunders were among the 48 survivors picked up by the Austrian steamer Jennie after 11 hours in the water and brought to Key West on October 19, 1906.

On April 6, 1907, Berte Parlin’s mother, Lucina, brother Fred, and sister Lizzie filed for probate for his estate in West Charleston, Orleans, Vermont. William J. Krome was appointed as administrator of the estate. Parlin’s homestead claim was patented on August 27, 1908, possibly by his brother, Fred L. Parlin, who was a resident of Florida City in 1940.

There are thousands of untold stories about the early history of this area. Using primary documents such as homestead records as starting points, it is sometimes possible to shed new light on the mostly forgotten early history of this area.

Incredible. 11 hours in the water. Now I have to read all the sub-articles within the main essays!

BTW: Jerry and Mary Lou are friends from Burton UMC in Tavernier. We are all very proud of his work over the years.

Jerry Wilkinson has done more for Keys history than anyone else that I know. He has helped me on a number of occasions – he’s a great guy!!