The Cutler Extension

by Jeff Blakley

Published histories of South Dade always mention the arrival of Flagler’s F.E.C. Railway in Miami in 1896 and the construction of the Key West Extension, which started in the spring of 1905. However, I’m not aware of any published account of the construction of the portion of the railroad between Miami and Homestead. Initially known as the Cutler Extension, it was renamed the Homestead Extension after it reached what became the Town of Homestead on July 30,1904.1

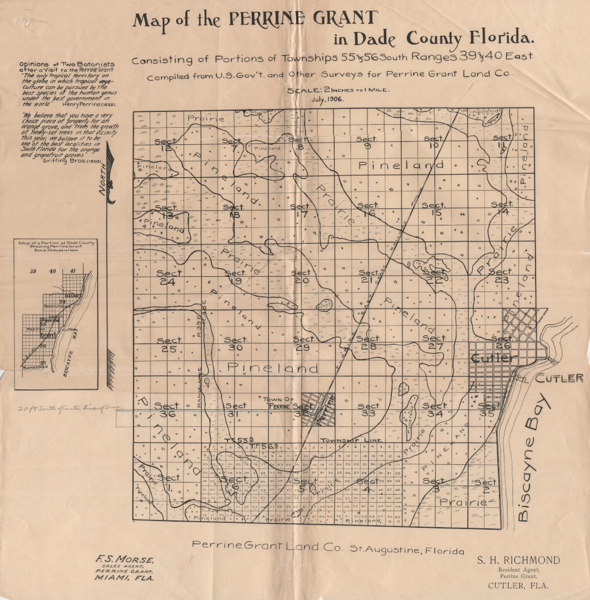

Flagler and some of the officers of his company had planned to take the railroad to Key West as early as 18932 but that information was a closely-guarded secret designed, no doubt, to prevent others from engaging in real estate speculation that would not be in the best interests of the Florida East Coast Railway. Flagler acquired a number of small railroads, starting in 1885. On May 28, 1892, he incorporated the Florida Coast and Gulf Railroad Company.3 In 1895, “Flagler changed the name of his railroad enterprises to the Florida East Coast Railway Company. The state approved the new company in September 1895…”4 After reaching Miami in 1896, Flagler did not authorize any more construction, likely because the ownership of the Perrine Grant, through which his railroad would ultimately pass, was unclear.

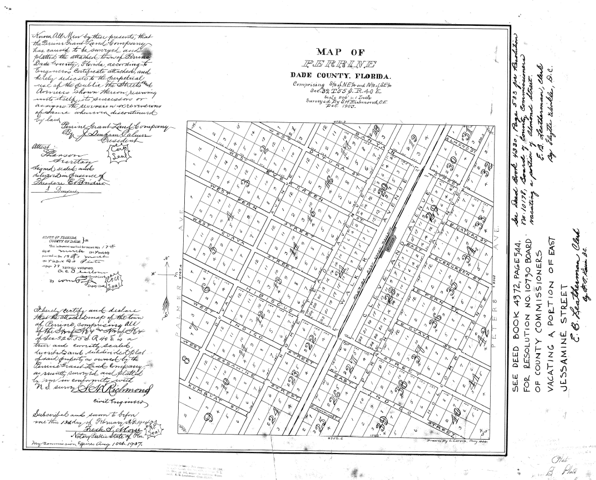

By 1899, though, the legal status of the Perrine Grant had been resolved in favor of the heirs of Dr. Henry Perrine and the F.E.C., so Flagler established the Perrine Grant Land Co. to manage the lands granted to Perrine,5 6 who had been killed by a party of Seminole Indians under the leadership of Chekika on the morning of August 7, 1840 on Indian Key.7

On July 2, 1902, a preliminary surveying party under the supervision of Aaron L. Hunt, assistant civil engineer of the F. E. C. Railway, left for Potter’s Mill,8 which was likely a sawmill on the homestead of Stephen S. Potter, part of whose land included what is now the main entrance to the University of Miami at Stanford Drive and Ponce de Leon Blvd. Potter had proved up his homestead claim on July 24, 1894.9 Hunt was in charge of the surveying party for two weeks, until John S. Frederick, the civil engineer who laid out portions of the City of Miami and also the platted the Town of Homestead, took over.10 John was a brother-in-law of George Kosel, an early pioneer in the Redlands, as his wife, Antoinette Gazzam Frederick, was the sister of Maria Gazzam, George’s wife.

John S. Frederick continued the survey down to below Homestead before returning to Miami late in the summer of 1902. William J. Krome then took over, making a more thorough survey in preparation for his survey of a possible railway route to Cape Sable, which he started in early October of 1902 and completed in June of 1903. Before leaving on his Cape Sable expedition, Krome had surveyed enough of the route to Homestead that crews in Miami could start work.11

Construction of the Cutler Extension started on the south bank of the Miami River shortly before January 30, 1903. Charles T. McCrimmon, who had the contract to clear the right-of-way for the railroad, “had 150 colored laborers … camped just south of the Miami River”12 clearing the right-of-way and constructing the railroad grade so that ties and rails could be placed by the track laying machine.

On the north side of the Miami River, another crew of workers had started work on the railway bridge.13 By April 1, 1903, all of the “huge timbers” that were to be used in the bridge had been placed for “several hundred yards on both sides of the track” and another crew on the south side of the river was “putting in piers for the bridge.”14

It took six months for the railroad bridge across the Miami River to be completed. On October 6, 1903, the first construction train crossed the Miami River. Captain Lucien Baker was the engineer in charge of the locomotive, which pushed a track-laying machine that was used by the crews placing the ties and rails. The right-of-way had already been cleared by McCrimmon’s crews and the grade was completed so the work of laying the rails proceeded rapidly.15

By April 17, McCrimmon’s crews had cut out the right-of-way down to Jackson Peacock’s homestead.16 This was near the present intersection of S.W. 22nd Avenue and U. S. 1. By the end of May, the grading crews had reached “DeBogory’s mill,” the location of which is unknown but had to have been further southwest. Peter DeBogory, a Russian immigrant, had claimed a homestead near Sanford, Florida, in 1883, where he was an orange grower. By 1900, he had moved to the neighborhood just outside the northern city limits of Miami, where he lived in an area heavily populated by African-Americans17 and worked as a machinist. His son, Alexander, established a bicycle repair and welding shop where the Miami Police station now stands in downtown Miami in 1916.18

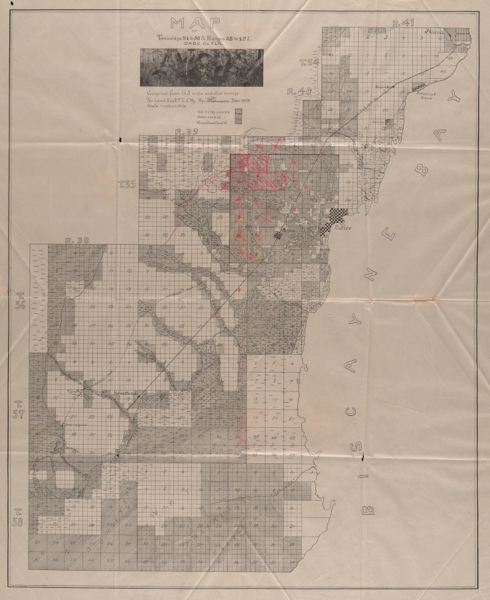

On September 25, 1903, The Miami Metropolis reported that E. Ben Carter, general roadmaster of the F.E.C., had authorized McCrimmon to proceed with the right-of-way clearing down to Long Key.19 The Long Prairie, shown a short distance below Homestead on the 1903 F.E.C. Railway land holdings map, crosses Krome Avenue just south of Lucy Street, the dividing line between Homestead and Florida City. “Long Key” seems to have been the name for all of the land southwest of the Long Prairie down to what is now known as Long Pine Key in Everglades National Park.20

Krome had returned from his Cape Sable expedition in late June of 1903 and he promptly picked up where he had left off in December of 1902, continuing the survey that John S. Frederick had started in July of 1902. On September 1, he and a party of men who had been camping out on lots adjacent to the offices of The Miami Metropolis, left for Black Creek,21 which was just south of the present day intersection of S.W. 211 St. and U. S. 1. The newspaper account said that he was going to work on the drainage project going on in that area at the time, but in reality, he was continuing the survey down to Homestead. Flagler and the top men of his company, including Krome, rarely spoke to newspaper reporters seeking more information about what they were doing. Krome and his crew reached Homestead by September 18, but were driven back to Modello, a few miles north, by a “heavy storm” which destroyed their camp. They had to fall back to their supply base in Peters.22 As this account was written in 1918, it is likely that the date of September 18 is incorrect, because The Miami Metropolis reported on a severe storm that struck Miami on September 5, being “the fiercest storm ever witnessed here in the memory of the oldest inhabitants.”23 That storm was very likely a hurricane.

McCrimmon and his crews completed clearing the right-of-way and grading the road bed down to Homestead by early March of 1904.24 Laying the rails from Miami to Homestead was all that remained to be done. That started on October 6, 1903 on the south side of the Miami River25 and advanced several miles each day, due to the use of the track-laying machine.

On November 13, The Miami Metropolis reported that “the railroad people are putting in a siding … 1,700 feet in length” at Perrine26 for Thomas J. Peters’ tomato packing business.27 The siding was graded and ready for the arrival of the track-laying machine, which had stopped on the north side of Snapper Creek on November 27, waiting for the crossing to be built across the waterway.28 This is the location of the Dadeland North Metrorail station today.

Flagler and the top echelon of the Florida East Coast Railway were closely monitoring the progress of the construction project. On November 27, 1903, The Miami Metropolis reported that James E. Ingraham had returned from an exploration trip of “several weeks” to the Long Key area and had secured 600 acres “in the heart of the homestead country” from the government in section 13, township 56 south, range 38 east “to be used for buildings, yards and other terminal purposes.” He was accompanied by William J. Krome, John S. Frederick, Frederick S. Morse, and Capt. Edward A. Graham.29 Frederick S. Morse was the F.E.C.’s land agent and the man in charge of selling the lands owned by the Perrine Grant Land and the Model Land Companies. Edward A. Graham was a mariner who captained not only several of the rear paddle-boat steamboats used in the construction of the Key West Extension, but was also the captain of the Enterprise, Ingraham’s personal yacht.

Courtesy of the Florida Pioneer Museum

Courtesy of the Florida Pioneer Museum

Edward A. Graham is the man pictured in the lower left corner of the photograph.

On December 18, Mr. Flagler and his wife, 4 top officials of the F.E.C. Railway, the mayor of Miami, John Sewell, the future editor of The Miami Herald, Frank B. Stoneman and B. B. Tatum left the Royal Palm Hotel in downtown Miami and traveled down to a point one-half mile north of No Man’s Prairie, where the track-laying machine stood idle, waiting for a trestle to be built across the finger glade.30 No Man’s Prairie was where Kendall Lexus, at 10775 S. Dixie Highway, is now located.

The track-laying machine was in the Perrine Grant on the first day of the new year,31 having traversed the Benson Prairie, where the Falls Shopping Center now stands, on a 400 foot long trestle32 and by February 5 it had crossed the Freeman Prairie,33 named after Dr. Mary Freeman, an early physician in Cutler and Perrine. The Freeman Prairie was located at S.W. 158th St. and U. S. 1 before the canal was dug and the prairie drained. By February 19, the tracks had been laid to the Peters Prairie,34 located between present day Quail Roost and Marlin Drives.

Below Peters, no newspaper articles have been found to document the progress of the track-laying machine. This is likely because the area was sparsely settled, with few homesteaders near the route of the railroad and no packing houses to ship produce. There were only 17 claims for homesteads in the sections traversed by the railroad south of Peters and only five of them were claimed before railroad construction started in 1903. With no audience to write for, the newspaper reported nothing about the progress of the railroad. In early March of 1904, McCrimmon and his crews had completed the clearing of the right-of-way, graded the roadbed to the future location of the Homestead depot35 and had returned to Miami.

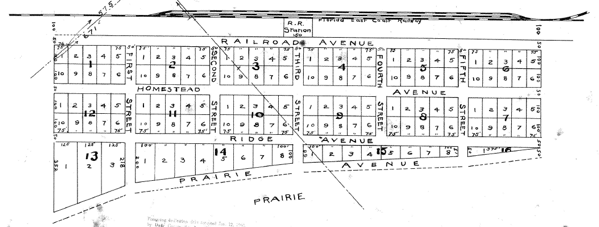

In June of 1904, shortly before the arrival of the rails, John S. Frederick completed the plat of the Town of Homestead.

The last rail for the Cutler Extension, now re-named the Homestead Extension, was laid on the afternoon of July 30, 1904.36 With the completion of the railroad to Homestead, the number of homesteading claims filed in South Dade increased substantially as new settlers realized the potential for becoming wealthy through investing in real estate. The goal of the F.E.C. Railway to open up the area for exploitation proved to be a success and doing so set the stage for Flagler’s next ambitious project: the building of the Key West Extension. Construction on that project started in Homestead in April of 1905 but also in several locations in the Florida Keys at about the same time.

______________________________________________________________

- The Miami Metropolis, August 5, 1904, p. 1

- The Evolution of the Key West Extension, by Jerry Wilkinson

- Flager: Rockefeller Partner and Florida Baron, Edward N. Akin, Kent State University Press, 1988, pp. 136-141

- ibid, p. 161

- ibid, p. 183

- Henry Flagler and the Model Land Company, in Tequesta, the journal of the Historical Association of South Florida, volume 56 (1996), pp. 51 – 52

- Robinson, T. Ralph, Tequesta, Volume II, pp. 18-19

- The Miami Metropolis, July 4, 1902, p. 1

- BLM Website

- The Miami Metropolis, July 4, 1902, p. 1

- Cape Sable Everglades Expedition, by Jerry Wilkinson

- The Miami Metropolis, January 30, 1903, p. 1

- The Miami Metropolis, March 20, 1903, p. 1

- The Miami Metropolis, April 3, 1903, p. 1

- The Miami Metropolis, October 9, 1903, p. 7

- The Miami Metropolis, April 17, 1903, p. 1

- 1900 U. S. census of Miami – search on Progore Debegorry, b. 1846 in Russia

- Obituary for Alexander DeBogory, Jr. in The Miami Herald, April 17, 2015

- The Miami Metropolis, September 25, 1903, p. 1

- See the essay written by Lilburn R. Nixon, which gives details about supplies being delivered to Camp East Point on Long Key. Lilburn R. Nixon — Early Pioneer Tales

- The Miami Metropolis, September 4, 1903, p. 2

- The Homestead Enterprise, October 24, 1918, p. 1

- The Miami Metropolis, September 11, 1903, p. 1

- The Daily Miami Metropolis, March 18, 1904, p. 1

- The Miami Metropolis, October 9, 1903, p. 7

- The Miami Metropolis, November 13, 1903, p. 3

- The Miami Metropolis, January 1, 1904, p. 8

- The Miami Metropolis, November 27, 1903, p. 3

- The Miami Metropolis, November 27, 1903, p. 1. “section 13, township 56 south, range 38 east” contains a typo – the township was 57, not 56.

- The Miami Metropolis, December 18, 1903, p.1

- The Miami Metropolis, January 1, 1904, p. 8

- The Miami Metropolis, December 18, 1903, p.1

- The Miami Metropolis, February 5, 1904, p. 3

- The Miami Metropolis, February 19, 1904, p. 4

- The Daily Miami Metropolis, March 18, 1904, p. 1. The roadbed was complete as far as Station 1500, which was Homestead.

- The Miami Metropolis, August 5, 1904, p. 1

Thanks Jeff, great addition to your previous research. Did your research yield any information as to when the wye was built behind the station and stretching toward Campbell Drive (NE 8th St)? The wye existed until the shopping center was built over it in the late 60’s.

Jeff your work is amazing!! Driving around our area keeps me engaged just thinking of how and why (what’s left) got there to begin with! And the location of all the thin box canals explains what their purpose was for. Draining of the prairies in the map of Perrine, the Falls, Southland areas etc.

But the Silver Palm/U.S.1 reference doesn’t appear to match Black Creek? Could it be more in reference to the Black Creek canal on US 1 by the new Walmart instead?

You are indeed correct, Alexis. Thank you for pointing out my error. I have corrected the article. The intersection of Silver Palm and U.S. 1 was the Caldwell Prairie and also the location of the settlement of Black Point, not to be confused with the location of the Black Point Marina, which is very close to the geographical location of Black Point.

As always an interesting and well researched addition to the history of the Homestead area. Initially, how much land did the FEC own and then how was it developed? Did the railroad sell land to the developers or developers sold it for the railroad. I’m assuming it owned more than it used for the tracks, buildings, etc.? Or, the land was homesteaded before the railroad was built and then the railroad bought it from the homesteaders, hence the need for secrecy so land prices wouldn’t inflate as you mention? Was the railroad granted eminent domain?

The short answer is that the Internal Improvement Fund, a State entity, granted railroad companies in Florida who promised to build trackage a varying amount of land per mile of track constructed. The same applied to canal companies. In the case of the F.E.C., Flagler established the Model Land Company in 1898 to manage the vast acreage granted to his company by the IIF. There was a clause in the deeds for homesteads that granted railroads a 200′ wide right-of-way for their tracks and that clause led to more than a few lawsuits, all of which were settled in favor of the railroad companies. The railroad companies were not granted eminent domain – they already had the right to build. To the best of my knowledge, there has not been much written about this, at least as it applied to the F.E.C. Contrary to the current favorable light cast upon the F.E.C., the company was widely despised by many people in the early years. The newspapers printed sarcastic letters and articles about “Uncle Henry” on plenty of occasions. The Florida Railway Commission was established in 1897 to deal with these complaints and cracked down on all of the railroads in Florida. The current picture of railroads in Florida is very biased in favor of the “big boys” as the history of railroad regulation in Florida seems to have been forgotten.

Thanks, Jeff. Interesting how government and individuals work together to bring civilization and services to the “wilderness”.

Well …. seems like there wasn’t much difference between “government” and “individuals” in those days, either! 🙂

Thank you, Jeff, for your diligence and most accurate chronicle of Homestead history. My family roots are embedded in the city and your account is enlightening. Curiously, while not directly related, John S. Fredrick appears to have made a contribution including the original plat. Looking forward to further articles.

Thanks for info and will check box to see notice of any reply.

Nice work, as usual, Jeff. Many thanks.

Thanks, Ed. I appreciate your support over the years. It’s been an interesting journey!