by Jeff Blakley

In Part I of this article, I presented the events leading up to the reservation of a plot of land for a graveyard in Homestead and showed its location. In this continuation of the series, I will show that the Model Land Co. and Dr. Tower, along with a lot of other men, were instrumental, for their own reasons, in the establishment of the South Dade Cemetery.

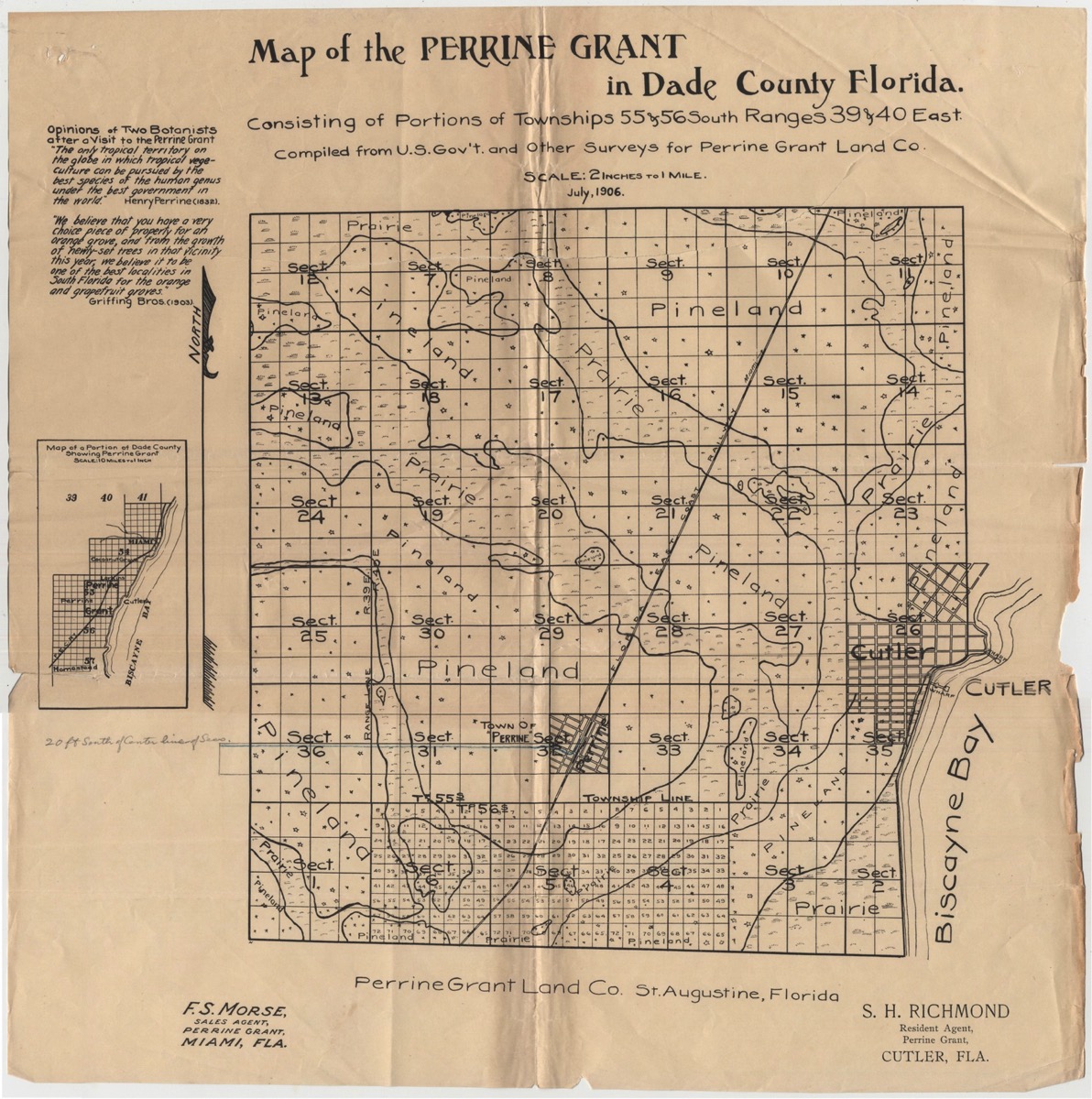

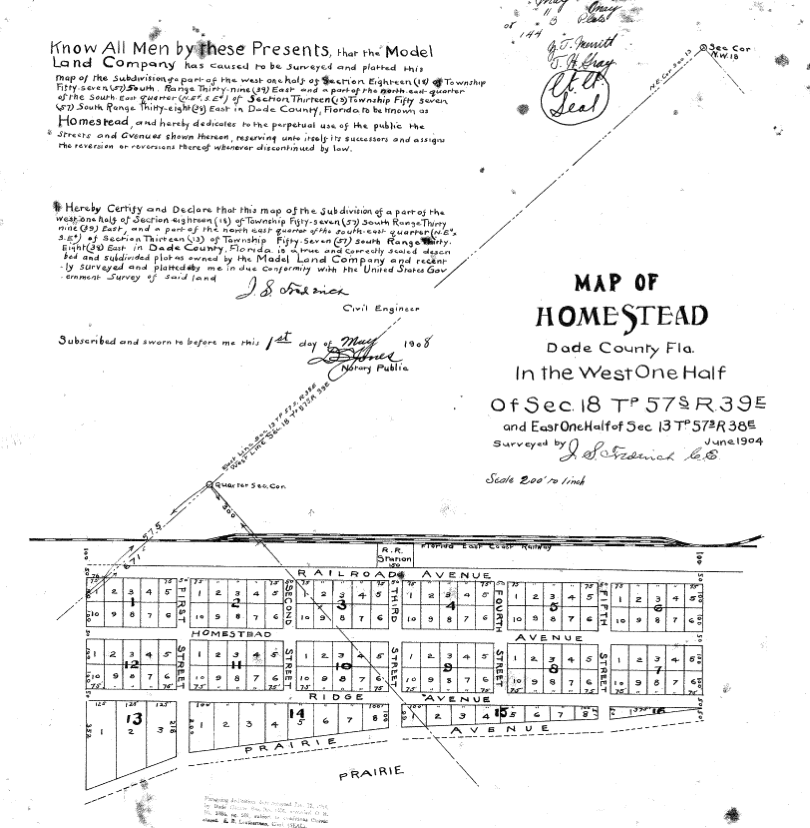

When John S. Frederick laid out Homestead in 1904, the Model Land Company had no way of knowing how rapidly the area would grow. In April of 1910, census enumerators counted 956 people in Homestead, Princeton, Redland and Silver Palm. Naranja and Goulds had no separate census district so it is unclear if those people were counted as part of Homestead and Princeton or if they were not enumerated. Even though a lot of people who died in the Homestead area were buried in the Miami City Cemetery or were shipped back to the town the deceased had come from, it was becoming obvious that a cemetery was needed.

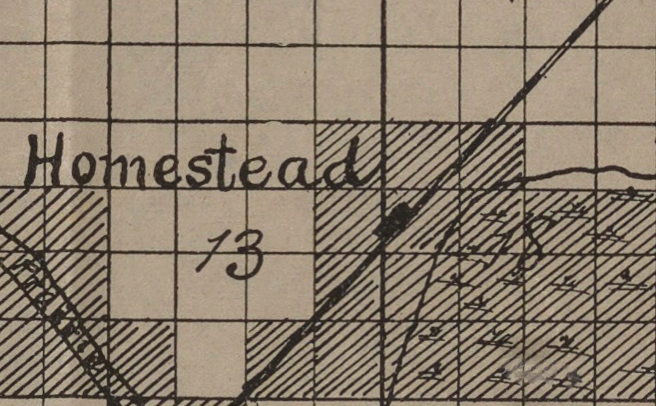

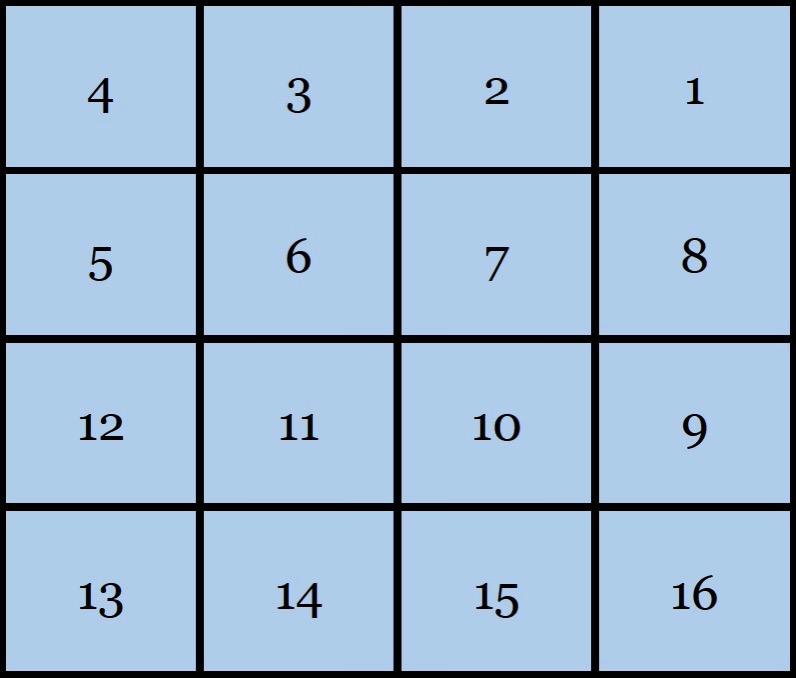

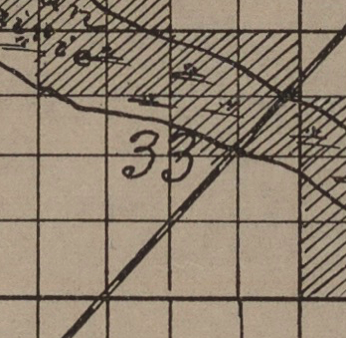

On October 11, 1911, Leonard S. Mowry, in response to Ingraham’s letter dated May 12, wrote to Fred Morse that “a committee of 5” had selected “block 14 in section 33-56-39,” for a graveyard, though the letter does not state that the land was going to be used for that purpose. The signatories were only 4: L. S. Mowery, G. W. Brown, C. W. Hill and J. M. Bauer. Mowry requested that the deed be issued to those four men.

The SW 1/4 of the NE 1/4, northeast of the second ‘3’

The SW 1/4 of the NE 1/4, northeast of the second ‘3’

On October 16, Ernest M. Horton, who had claimed the 160 acres south of lot 14 (the SE 1/4 of the NE 1/4 of 33-56-39) on September 4, 1908, wrote to Morse on the stationery of the Riverside Grocery Company, located at 503-505-509 Riverside Avenue in Miami, objecting to Mowry’s selection. He stated that “the location of the cemetery on this lot would do me great injury, besides not being as well adapted as the ten acres lot 13, joining this on the west.” Horton’s homestead was bounded on the north by S.W. 272 St., on the east by S.W. 147 Ave., on the south by S.W. 280 St. and on the west by S.W. 152 Ave.

Mowry apparently did not agree with Horton, as he circulated a petition asking the Model Land Co. to set aside lot 14 for a cemetery. It was signed by 52 people from all over the Redland District. In that document, the reason given for the change in location from Homestead was “that the land now used for that purpose being, that the ground at the present location is so low that it is not at all a fit place to bury a body, and the water percolating through the cemetery contaminates the water supply of the whole Town of Homestead to the great detriment of the general health. In the new location selected these objections are overcome as the ground is very high and consequently dry.”

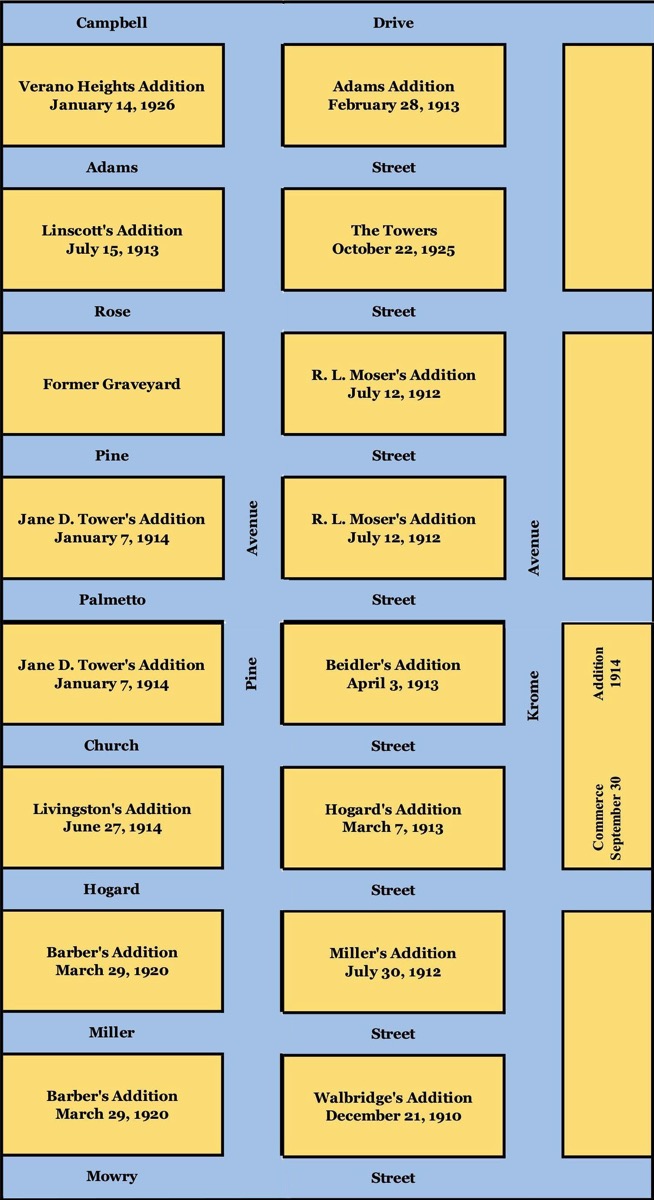

There were at least two undertaking companies in Miami – W. H. Combs and H. M. King. Neither had a Homestead branch until the King Undertaking Co. established a branch in Homestead in 1921.1 It is likely that both companies provided undertaking services to the Homestead area, but the only evidence for that is a bill paid by the Town of Homestead on April 7, 1914 to H. M. King in the amount of $7.94.2 Bodies were sent to Miami, prepared for burial and then shipped back to Homestead on the train. Negative public opinion was no doubt amplified by the authoritative voice of medical doctors, including Dr. Tower. There were other doctors living in the Homestead area, among them Dr. John Dennis in Modello, Dr. Edward L. Brooks in Homestead and Drs. Benjamin F. Forrest, Thomas W. Shields and Stuart S. Shields in Detroit. The contributions of these other doctors to the debate are unknown but there were only a few bodies buried in the graveyard and no one lived nearby as the subdivisions surrounding the burial ground had not yet been platted. The stated reasons in the petition mirrored the concerns of Morse and Ingraham but it is likely that the real reason for locating the cemetery far away from Homestead had more to do with real estate speculation and land values, not a concern over the health of the residents. Dr. John B. Tower purchased 15 acres of land “near the station” in November of 1911,3 nine months after the body of Mrs. Charles R. Williams had been interred in the nearby cemetery.4 The ten acres immediately south of the cemetery, which became the Jane D. Tower Addition to Homestead, was platted in late 1913. How many other bodies were interred in the cemetery is unknown, but might be discovered by conducting a survey using ground penetrating radar.

In a letter to Ingraham dated November 22, 1911, Morse alluded to what we now call the Not In My Back Yard syndrome by writing, “I presume there will be objections by neighbors, but that we should hear from later.” He did indeed hear from a neighbor, one Ernest M. Horton. But the real estate speculators in Homestead were happy and the Model Land Company knew that it could deal with one protestor much more easily than 52, many of whom were prominent citizens 5 who were in a position to make life difficult for the F.E.C. It was a win-win situation for the Model Land Company.

Note that Dr. Tower and his wife, Jane D., owned two city blocks (10 acres) very close to the cemetery and Ruben L. Moser, an early pioneer in Longview and a neighbor of Dr. Tower in Topeka, Kansas and in Longview, also owned two city blocks (10 acres). In 1913, Dr. Tower and his wife lived on what was platted as The Towers Addition (5 acres) in 1925.

A perusal of the names on the petition submitted to the Model Land Company show the names, in addition to Dr. Tower, of Charles Hammond, owner of a meat market; William A. King, the F.E.C. section foreman in Homestead; John U. Free, who left his fingerprint on everything in the area; J. D. Redd, the Homestead councilman and future County Commissioner; David W. Sullivan, owner of the Southern Pines Hotel; Joseph Cormack, merchant and Methodist minister; Edward Walbridge, the attorney who platted the Walbridge Addition, Thomas Evans, owner of the Redland Hotel; Edward Brooker, future town marshal; Henry Brooker, Sr., future lumber yard owner; Oscar Strickland, future Justice of the Peace; Leonard Mowry and Patrick Lamb, a future elector for the Town of Homestead. All of these men were prominent individuals and had plenty of money and power. This is the explanation for the change in the location of the cemetery, not a fear of disease. The public furor created over the threat the cemetery presented to drinking water supplies was a minor and convenient excuse to provide cover for real estate speculators.

In the final part of this series, I will provide the details surrounding the establishment of the Palms Cemetery in Naranja.

Click here to continue reading Part III

_____________________________________________________________